One morning in mid-2018, a hush fell over the factory floor at Mid Continent Nail Corporation in Poplar Bluff, Missouri. The plant manager had grim news: dozens of workers were being laid off on the spot as orders for the company’s nails abruptly dried up. Shock and confusion rippled through the crew gathered on the assembly line – how could demand for something as essential as nails vanish virtually overnight? The culprit turned out to be an unexpected spike in steel prices after a new 25% tariff on imported steel took effect, driving up the factory’s raw material costs and forcing it to raise prices. Mid Continent’s biggest customers found cheaper foreign suppliers and cut their orders, leaving this small-town American factory in crisis.

For Mid Continent Nail – the largest U.S. producer of nails, responsible for half of all nails made in America – the tariff proved an existential threat. The company suddenly had to pay significantly more for the imported steel wire it uses to make nails. To cope, it hiked its prices, hoping customers would understand. Instead, many simply switched to imported nails that weren’t subject to the extra duty. In a mere two weeks, the factory lost roughly half its orders. Sales eventually plummeted nearly 60%, and the workforce shrank dramatically – from about 500 employees down to 300 – as layoffs and attrition piled up. A policy meant to revive U.S. metal industries was now pushing this proud American manufacturer to the brink of closure, a scenario few in Poplar Bluff ever imagined.

On the factory floor, the impact was heartbreakingly personal. Veteran employees who had spent decades at the plant packed their tools and belongings into cardboard boxes, unsure if they would ever return. Mid Continent had been one of the town’s biggest employers – the second largest in an area of 17,000 people – so each lost job sent shockwaves through families and local businesses. “We are suffering,” admitted Chris Pratt, the general manager, describing how the company was “losing money every month” as a direct result of the tariff. He even lamented that his factory had become “an unintended consequence” of national trade policy– a casualty of a well-intentioned economic decision. For the folks in Poplar Bluff, the debate over tariffs isn’t abstract: it’s unfolding in the quieted aisles of their once-booming nail plant and the kitchens of workers wondering what tomorrow will bring.

This human story of a nail factory in Missouri offers a glimpse into the real-world ripple effects of tariffs. It illustrates how a sweeping trade measure – aimed at protecting some industries – can unexpectedly upend others, turning lives and local economies upside down. As we turn to a deeper analysis of the economic costs and benefits of tariffs, the experience of Mid Continent Nail Corporation provides a poignant reminder of what’s at stake beyond the statistics and politics. It’s a story of families, jobs, and communities caught in the crossfire of economics – a narrative entry point into understanding tariffs’ true impact on everyday people.

Basic Facts

Tariffs are taxes levied on imported goods at a country’s border. By raising the cost of foreign products, tariffs aim to protect domestic industries and can also generate government revenue. They were once a primary revenue source for the United States (before the income tax in 1914) and remain important in some developing countries. In recent years, tariffs have re-emerged as a prominent policy tool – for example, the U.S. imposed wide-ranging tariffs in 2018–2019 after decades of declining trade barriers. This report provides an in-depth, unbiased analysis of the economic costs and benefits of tariffs, focusing on the U.S. economy with global examples. It will cover:

General economic effects of tariffs – how tariffs affect prices, efficiency (deadweight loss), and inflation.

Tariffs vs. other taxes – comparing tariffs to income, sales, and corporate taxes in efficiency and economic impact.

Potential benefits of tariffs – the infant industry argument and strategic long-term gains (as in Paul Krugman’s economies-of-scale models).

Empirical evidence and case studies – including the U.S. “trade war” tariffs of the late 2010s and examples like China’s use of tariffs in industrial policy.

Throughout, we cite empirical research and historical cases to weigh the costs and benefits objectively. Tables and structured sections are used for clarity.

Economic Effects of Tariffs: Prices, Deadweight Loss, and Inflation

Tariffs operate like a sales tax on imported goods, raising their price in the domestic market. This has several general effects on the economy:

Higher Prices for Consumers: A tariff on an import causes the price of that good (and its domestic substitutes) to rise by roughly the amount of the tax. Domestic producers, now shielded from cheaper foreign competition, can increase their prices up to the level of the taxed import. For example, after a 25% U.S. tariff on steel in 2018, American steel producers quickly raised prices, with one citing that demand “came on so fast that we had to raise our prices”. Consumers end up paying more for both imported goods and for domestically made alternatives, reducing their real income.

Producer Gains and Production Distortions: Domestic firms competing with imported goods benefit from the tariff through increased sales and higher prices. In the steel example, U.S. steel mills saw a surge in orders and could sell at higher prices. However, these gains for protected producers come at the expense of other firms and sectors. Industries that use the tariffed item as an input face higher costs –as in the case of Mid Continent Nail Corporation.. Resources are diverted into the tariff-protected industry (steel, in this case) and away from more efficient uses. This misallocation means the economy produces some goods at higher cost domestically rather than importing them more cheaply, a core inefficiency caused by tariffs.

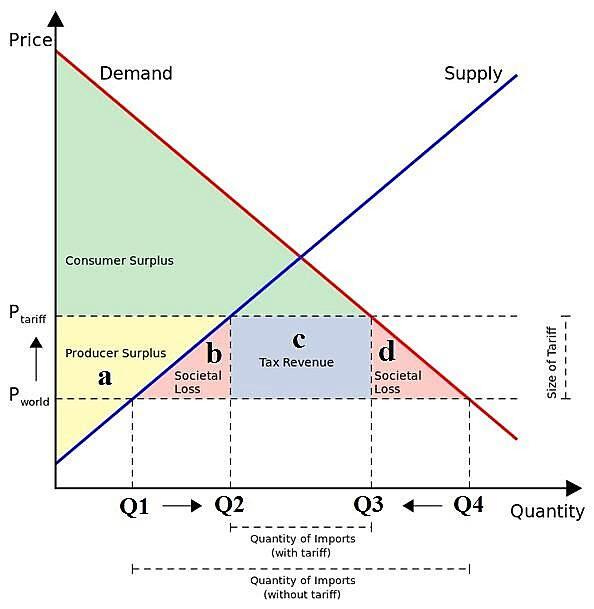

Deadweight Loss (Efficiency Loss): Like any tax, a tariff creates a deadweight (societal) loss – lost economic welfare that is not transferred to anyone but rather disappears due to reduced trade and consumption. Because voluntary trades that would benefit buyers and sellers are prevented by the tariff’s higher price, overall welfare falls. Economists note that tariffs tend to create more deadweight loss than broad domestic taxes because tariffs are discriminatory, altering the allocation of production between domestic and foreign sources. In essence, tariffs protect higher-cost domestic production, so society expends extra resources to make goods that could have been obtained more cheaply through trade. One analysis finds that tariffs are “paradigmatic” in reducing economic efficiency by precluding mutually beneficial exchanges. The cost of this inefficiency can be substantial. For example, research on the U.S. 2018 tariffs by Amiti, Redding, and Weinstein found U.S. consumers and importers paid about $3 billion per month in tariff taxes and suffered an additional $1.4 billion per month in deadweight loss – a pure loss of output and welfare. In other words, every dollar of tariff revenue came with roughly 50 cents of lost economic efficiency in that episode. Figure 1 illustrates the concept of deadweight loss in a tariff: consumers lose more in surplus than the government gains in revenue or domestic producers gain in profits, with the remainder being the net welfare loss to the economy.

Figure 1.

One-Time Inflationary Impact: By raising the prices of affected goods, tariffs can contribute to a higher price level – essentially a one-time inflation in the cost of certain products. Empirical studies of the 2018–2019 U.S. tariffs found a near-complete pass-through of tariffs to import prices, meaning import costs rose essentially dollar-for-dollar with the tariffs. Many imported consumer goods (from appliances to electronics) became more expensive for Americans. In some cases, prices rose even more than the tariff rate (a phenomenon called over-shifting): for instance, a $1 increase in U.S. tariffs on imported solar panels raised final installation prices by $1.34 as domestic suppliers took the opportunity to increase their margins. Higher import prices can feed into consumer price inflation if the goods are a significant part of household consumption. Indeed, U.S. price indexes for tariffed categories (like washing machines) jumped after tariffs were imposed. However, the overall inflationary effect of tariffs is usually modest if the tariffed goods make up a small share of the economy. Tariffs mainly change relative prices (making imports relatively more expensive) rather than fueling ongoing inflation across the board. In the 2018 U.S. trade war case, even though tariffs of 10–25% were placed on hundreds of billions of dollars of imports, those imports were still a fraction of total consumer spending. The result was a noticeable but limited uptick in inflation – essentially a one-time level shift. Over time, some importers and retailers absorbed part of the costs (accepting lower profit margins initially), and others found alternative suppliers in non-tariffed countries to mitigate price increases. In summary, tariffs tend to raise prices in the short term, but unless continually increased or broadened, they do not create sustained inflation like a macroeconomic demand shock would. They do, however, reduce consumers’ purchasing power similarly to a sales tax or a price hike, which can dampen real consumption.

Retaliation and Secondary Effects: Although not an intrinsic effect of a single tariff, in practice, tariffs often invite retaliation from trade partners. If Country A raises tariffs on Country B’s exports, Country B may respond with its own tariffs. This can escalate into a trade war, multiplying the disruption. Exports can suffer (foreign tariffs hit domestic exporters), and global supply chains may be re-routed. For instance, U.S. exporters of agricultural products faced retaliatory tariffs in 2018–2019, leading to lost sales abroad and requiring government aid to farmers. Tariffs can also induce currency adjustments – e.g. the tariffed country’s currency might depreciate – partially offsetting the tariff’s impact but affecting other sectors like exports. Economists note that a tax on imports can indirectly act like a tax on exports in general equilibrium. These broader effects reinforce that while some industries gain from protection, others (especially exporters and import-using industries) are harmed, and the net national effect is usually negative in terms of efficiency and output.

In summary, the general economic impact of tariffs includes higher prices for consumers, protective effects for certain domestic producers, and a net efficiency loss due to distorted production and consumption. Tariffs can cause deadweight losses that shrink overall economic welfare. They also risk cascading effects like retaliatory trade barriers and politicized lobbying (as companies seek exemptions or higher protection. The short-run benefits (profits and potentially jobs in protected industries) must be weighed against these wider costs on consumers and the economy’s allocation of resources.

Tariffs vs. Other Taxes: Efficiency and Inflation Comparison

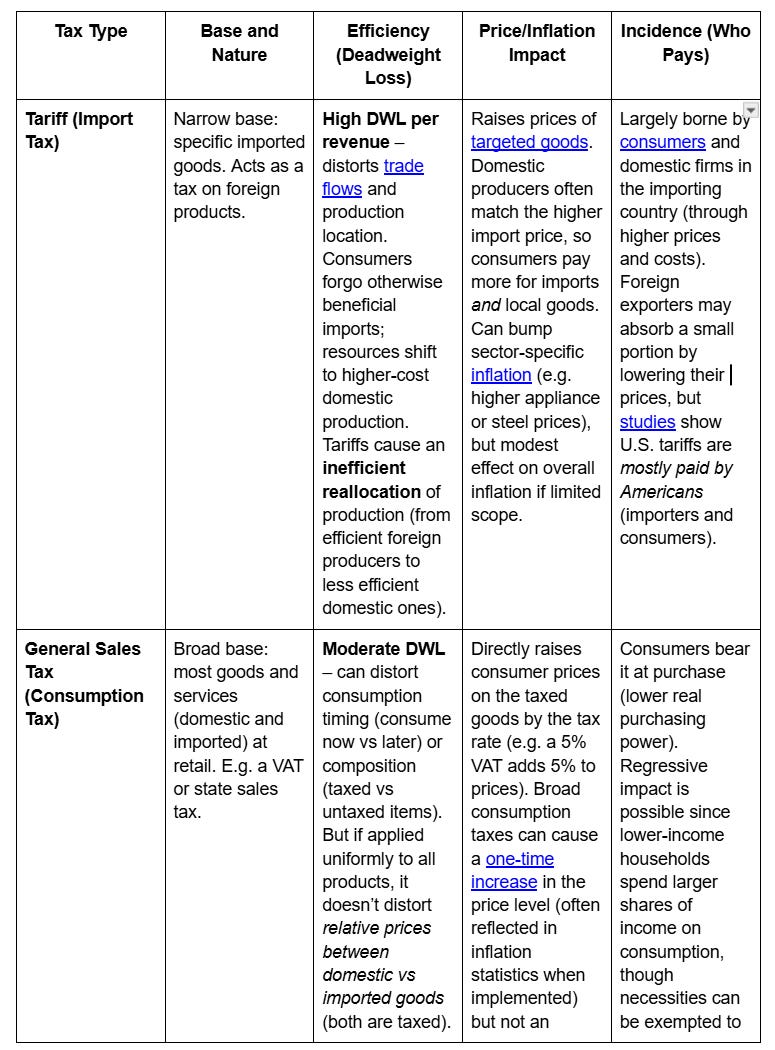

Tariffs are one form of taxation. It is useful to compare them to more common taxes – such as income taxes, sales taxes, and corporate taxes – in terms of efficiency (deadweight loss) and impact on prices/inflation. Table 1 summarizes key differences:

Table 1: Comparison of Tariffs and Other Taxes on Efficiency and Prices. (DWL = deadweight loss).

As Table 1 suggests, tariffs generally rank as a less efficient form of taxation compared to broad-based taxes. The discriminatory nature of a tariff (taxing foreign goods but not the equivalent domestic goods) causes consumers and firms to shift behavior in especially distortionary ways. In fact, economists have pointed out that tariffs create more deadweight loss than many internal taxes for a given amount of revenue. One reason is that part of the cost to consumers from a tariff goes not to the government (as revenue) but to domestic producers in the form of higher prices, and another part is simply lost by shrinking the overall volume of trade. For example, U.S. tariff revenue in fiscal year 2024 was about $77 billion, but consumers paid much more than that in higher prices– the difference being the combination of transfers to producers and deadweight losses in consumption. By contrast, a domestic sales or income tax of $77 billion would transfer money to the government but wouldn’t specifically raise the price of one product relative to another or protect a higher-cost producer.

In terms of inflationary impact, a tariff is akin to a sales tax on a subset of goods – it directly makes goods more expensive for end-users, which can register as a higher Consumer Price Index (CPI) for those items. Broad sales taxes (like a VAT increase) similarly cause a one-off rise in the price level. Income and corporate taxes, on the other hand, work through disposable income or profits and do not directly drive consumer prices up. In fact, if one were to replace a broad-based tax with tariffs, it could be more inflationary because the tax burden would shift onto goods prices. For instance, analysts noted that proposals to finance U.S. government revenue with across-the-board tariffs (in lieu of, say, income taxes) would amount to a noticeable price hike on nearly all imported consumption – effectively a tax visible to consumers at the checkout. Each tax type also has different incidence and equity implications: tariffs are often considered regressive (lower-income households pay a larger share of their income on tariffs, since many essentials like apparel or food can face tariffs), similar to sales taxes. Income taxes can be made progressive. Thus, from a policy perspective, tariffs are usually not the first-choice tax for raising revenue in a large, advanced economy – they distort trade and typically provide a relatively small share of revenue (only ~1.5% of U.S. federal revenues in 2024). Developing countries may rely more on tariffs due to easier collection at ports, but this can come at the cost of higher consumer prices and inhibited trade growth.

Part Two: Benefits of Tariffs and Empirical Evidence Here…

Notes: This is not a solicitation to buy or sell any stock. Feel free to send me corrections, new ideas for articles, or anything else you think I would like: cameronfen at gmail dot com.

If you are interested in listening to a (AI distilled) podcast on this article instead of reading, some of my articles will be posted as podcasts https://www.youtube.com/@cameronfen203. Unlike the articles, I have not listened to and fact-checked the podcast output. AI models are known to hallucinate information and even if it’s based on something factual, I encourage you to approach the podcast as entertainment and keep a skeptical eye out for fake news. Please like and subscribe here and on the youtube if you feel like it’s a worthwhile resource, as it helps other people find the blog. Let me know if you want more articles uploaded as podcasts.