Flying Suitcases of Hard Drives: The Chinese Playbook on How To Dodge US Chip Bans

The AI battle between China and the US

Related Article: AI, Techbros, and Communism

Four Chinese AI engineers step off a plane in Kuala Lumpur. Each carries a suitcase — not of clothes, but of hard drives filled to the brim with training data. Together, they haul roughly 4.8 petabytes of data (about 4,800 TB) through Malaysian customs, concealing it in four separate bags to avoid suspicion. At a local data center, they rent hundreds of Nvidia-powered GPU servers and feed those servers their data to train a cutting-edge AI model, which they later carry back to China. This almost analog gambit – physically moving data instead of smuggling chips – has become a subtle but widespread workaround to U.S. export controls on AI hardware. The stunt, reported by the Wall Street Journal, illustrates the lengths to which Chinese tech firms will go to keep pace in the global AI race.

The episode opens a window onto a broader game of cat-and-mouse. Since late 2022, the U.S. has imposed strict export controls on advanced semiconductors – especially high-end AI chips like Nvidia’s A100 and H100 GPUs – to curb China’s ability to build powerful AI and supercomputers. These measures aim to “choke off China’s access to the future of AI and high-performance computing”, a national-security strategy to prevent Chinese military or surveillance tech from getting too powerful too fast. But as engineers in Malaysia and other hubs are proving, determined companies can find loopholes. By moving data out of China and tapping foreign servers, they sidestep the literal hardware ban while still using U.S.-designed chips abroad.

In one instance, four engineers flew in 15 hard drives each from Beijing to Malaysia, totaling about 4.8 PB of AI training data. They then plugged the drives into 300 Nvidia GPU servers rented at a Malaysian data center to train a large language model, later bringing back only the trained model parameters to China. This ad-hoc “data laundering” – exporting the data instead of the chips – completely skirts the letter of U.S. export law. “Instead of moving hardware… developers sneak out raw data and return with trained models, sidestepping controls entirely,” notes one report. In effect, the heavy computation happens overseas on legally purchased chips, while China’s AI firms simply retrieve the results.

U.S. Chip Curbs and Their Purpose

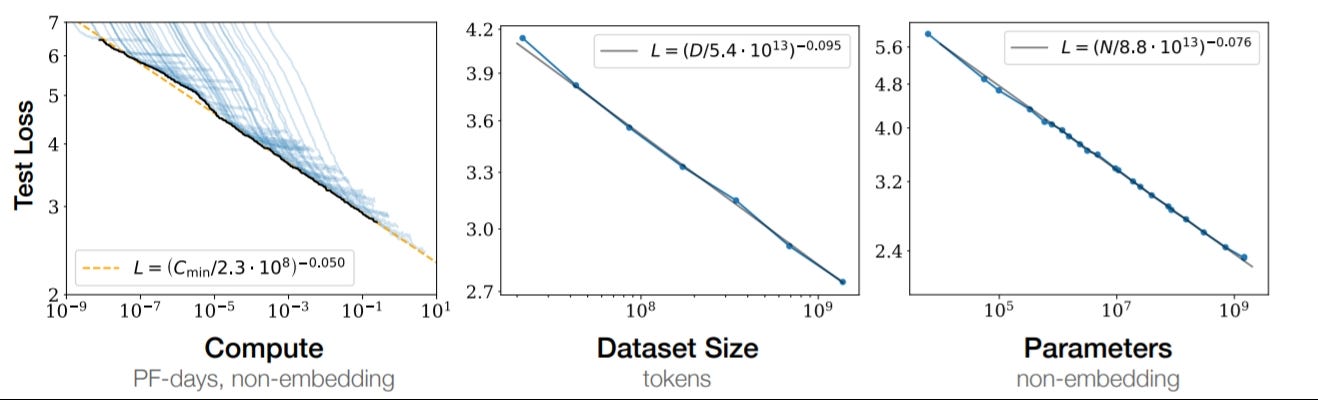

The above graph ranks the Nvidia GPUs that are used to train advanced AI models. Note that the most recent models are even more effective in inference and 8-bit quantization

The backdrop to this subterfuge is a series of U.S. export restrictions on advanced computing gear. In October 2022, the Biden administration banned exports of leading-edge Nvidia GPUs (like the A100 and H100) and other high-performance processors to China, citing national-security concerns. These chips are the beating heart of modern AI and supercomputing. According to a CSIS analysis, the rules target precisely “the A100, H100, and Blackwell… GPUs made by Nvidia” and related technologies. The goal is to degrade China’s AI industry by cutting off its access to the most powerful hardware. A follow-up crackdown in October 2023 extended controls further, essentially embargoing the modified A800/H800 chips (China-market versions of A100/H100) and other high-end GPUs.

Strategically, U.S. policymakers see these controls as a way to stay ahead in the AI “arms race.” As one policy report puts it, the measures aim to (1) choke off China’s access to the next generation of AI and high-performance computing, (2) block China from making its own equivalent chips, and (3) allow some sale of mid-tier technology so U.S. chipmakers aren’t unduly harmed. In short, Washington wants to slow China’s rise by keeping game-changing AI hardware out of its hands, even as it tolerates older chips still flooding the market.

But hardware is only part of the picture. Modern AI training also depends on vast data and computing power. The new export regime does not restrict data – and here China has gotten creative. Instead of shipping chips, Chinese developers are now shipping data.

Flying the Data Out

While the so-called scaling laws are now a bit outdated, these laws can tell you the performance you can approximately get given the number of parameters, dataset size, and compute. Thus, Chinese AI firms can approximate performance of their models before even training.

With top GPUs off-limits, Chinese AI firms have begun booking the flights themselves. In a careful operation, one company spent eight weeks pre-processing and optimizing its AI training data in China. Then, as one report details, four engineers flew to Malaysia with 15 portable drives each, packed with 80 TB apiece. Transporting 4.8 PB of data over the internet would take months and risk detection; stuffing it into suitcases was faster and stealthier. At customs, the drives were dispersed among four passenger bags to avoid "raising alarm bells".

Once in Kuala Lumpur, the engineers plugged their disks into rented servers. They had arranged to rent 300 Nvidia GPU servers at a Malaysian data center through a local subsidiary. Running the data on those GPUs, they trained their large AI model offshore. After training, the team carried back only the model parameters — a few hundred gigabytes of results — safely within China’s borders. In effect, the heavy lifting was done on U.S. chips legally purchased overseas, and China got only the "brain" of the AI model home.

This method isn’t a one-off stunt. The Wall Street Journal describes it as a “meticulously planned operation” reflecting months of prep. Moneycontrol reports that several Chinese AI developers have taken to processing their data abroad, in places like Southeast Asia and the Middle East, to keep using American chips despite the bans. Malaysia has become a particular hotspot. Data-center capacity in Southeast Asia is exploding – with about 2,000 megawatts of capacity in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia combined, rivaling Europe’s largest markets. In Singapore and Malaysia, Chinese entities find both technical infrastructure and relative legal ambiguity.

Shell Companies and Fronts

The data flights are only one piece of the puzzle. Chinese firms also use a web of corporate shells and local partners to muddy the trail. According to investigative reports, Chinese AI companies have set up Singapore or Cayman-island subsidiaries to negotiate rentals and purchases, keeping the parent company’s identity out of sight. In one case, a Malaysian data center initially leased gear to a Singapore-registered subsidiary of a Chinese firm. But when export controls stiffened, local authorities insisted on a Malaysian-registered front. The Chinese developers dutifully incorporated a Kuala Lumpur entity (with Malaysian directors and an offshore holding parent) to satisfy regulators.

These legal maneuvers turn nodes of corporate paperwork into loopholes. By hiding the end user behind a benign-looking local address, U.S. companies (or their overseas subsidiaries) can claim compliance. As a Fudzilla report explains, this keeps the chipmakers “technically in the clear while Chinese users stay at arm’s length”. China’s AI community even has a term for the technique: they’ve started joking about “smuggling suitcases full of data” instead of hardware. Importantly, no U.S. chip or software is exported to China in this scheme, so it doesn’t violate the letter of the restrictions. The raw data leaves China, but that isn’t controlled by law.

The use of fronts and middlemen extends to hardware purchases too. A Reuters analysis of government tenders found Chinese universities still getting top Nvidia chips via resold servers from companies like Dell and Super Micro. In that case, China’s buyers and local resellers exploited pre-existing stock or subtle supply-chain gaps. U.S. enforcement agencies have even noted a proliferation of “shell companies” involved in chip shipments. This underscores that wherever there’s demand and profit, companies will find ways: mixing legal subsidiaries, offshore companies, or intermediaries to obscure the true destination of technology.

Cloud and the Sky’s the Limit

Another bypass has been the cloud. While export rules target physical hardware, they generally allow remote use of U.S. cloud services outside China. American firms like Amazon, Microsoft and Google offer “AI on demand” in overseas data centers – effectively renting Chinese users the virtual use of U.S. chips. In mid-2024, Reuters reported that Microsoft’s Azure and Google Cloud were letting Chinese companies sign up to servers with A100/H100 GPUs located abroad. One account noted China’s customers access these foreign data centers through local partners, with each cloud provider insisting it is complying with all trade laws.

This loophole is substantial. A Reuters investigation found at least 11 state-linked Chinese entities seeking AWS, Google, or Alibaba cloud accounts specifically to tap Nvidia AI chips they couldn’t buy outright. For example, Shenzhen University paid about $28,000 to a local reseller for AWS time on A100 and H100 servers abroad. By contrast, these transactions weren’t counted as “exports” of chips to China, because the actual silicon never crossed Chinese borders; the only thing delivered was computing time over the internet.

Washington is aware of the cloud backdoor. In Congress, lawmakers have called remote-cloud access a “loophole” that must be closed. U.S. foreign-policy chief Michael McCaul, for instance, said he has “long [been] concerned” about overseas cloud use by Chinese AI developers. In spring 2025, the administration signaled plans to extend export rules to cover remote access – though details remain in flux. For now, Chinese firms can still execute their AI jobs on American chips via the cloud, underscoring the challenge of policing software as strictly as hardware.

Southeast Asia’s Quiet Boom

Asia-Pac demand for GPUs is set to grow exponetials both as countries get richer and as China uses neighbors for backdoor access to US chips

The story isn’t just about Chinese ingenuity; it’s also about geography and economics. Southeast Asian countries have unintentionally become a new frontier in the global semiconductor tug-of-war. Malaysia, in particular, has seen a massive spike in chip imports. In March–April 2025 alone it imported $3.4 billion in processors from Taiwan – more than its total for all of 2024. Much of that is believed to be GPUs and other AI-focused chips destined for data centers. Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia have also expanded high-speed data-center capacity. A Jones Lang LaSalle report estimates the region’s capacity now rivals major European markets.

For Chinese AI developers, this growth is a gift. They can set up accounts or local teams in these countries and tap state-of-the-art infrastructure. Even U.S. chip makers see the trend: Nvidia’s CEO boasted of “cloud partnerships” and recently inked multi-hundred-thousand-chip deals with Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE to build AI centers. The effect is to push raw computing power into regions that serve Chinese demand without directly violating U.S. law. One Malaysian investor in AI servers notes that business is booming – entrepreneurs poured millions into GPU farms aimed at Chinese clients.

Yet the host countries walk a diplomatic tightrope. The U.S. has quietly urged Malaysia and Singapore to help police chip flows. In early 2025, Malaysia announced it would track every shipment of high-end Nvidia chips entering its ports, at Washington’s insistence. Trade Minister Zafrul Aziz explicitly said the U.S. wants Malaysia to monitor GPU shipments closely, and to make sure servers “end up in the data centers that they’re supposed to and not suddenly move to another ship”. Meanwhile Singapore’s government has aggressively cracked down on illegal server exports. In one case this spring, Singaporean courts charged people for disguising Nvidia servers bound for China.

Even so, the net is porous. U.S. attempts to impose country-specific limits have been stymied. The Trump administration in 2024 dropped a plan to cap chip exports to places like Malaysia, preferring voluntary guidelines. As a result, Southeast Asia remains a gray zone: an ethical “no man’s land” where Chinese money meets American technology under local oversight that is still catching up.

The Great AI Race

What does all this mean for global tech policy? The situation underscores a fundamental tension: no matter how strict Washington’s controls, the nature of AI development – which fundamentally requires data and compute – means workarounds are hard to stamp out. As one export-control expert noted, the US was always “consistently concerned” about Chinese firms finding ways to run on American chips remotely. The hard-drive flights and cloud rentals are vivid proof of that concern.

For U.S. policymakers, the clever evasions signal that hardware bans alone may not be enough to slow China’s AI ambitions. Every innovation on one side (the ban) invites a counter-innovation on the other (data flights, shells, cloud). This dynamic plays into the broader “AI arms race” – countries vie not just for the best chips, but for the smartest use of data and alliances. Experts argue the U.S. must perhaps rely more on diplomacy and alliances. For example, lines have been drawn to restrict not only direct sales to China, but also the use of U.S. equipment in foreign factories (the Foreign Direct Product Rule). And new rules may eventually close the cloud loophole by treating it as an export of a service rather than just hardware.

For China’s part, the push to outflank U.S. controls may accelerate its own industry. Chinese firms are already ramping domestic alternatives (lower-end chips, or indigenous GPUs), as well as stockpiling whatever they can abroad. The Reuters report on Nvidia’s tailored China chips (the cheaper Blackwell model) shows China remains a lucrative market that US companies want back in. Meanwhile, Chinese semiconductor champions like SMIC and Huawei watch these developments closely, aware that any sustained gap in cutting-edge hardware could be a critical disadvantage.

A Delicate Balance

Ultimately, these developments raise complex questions for global security and trade. Critics of export controls caution that aggressive bans could backfire if allies or companies find them too onerous – or if the market simply diverts elsewhere. The Commerce Department itself admitted enforcement is underfunded relative to the challenge. Others argue that as long as there’s a global network of commerce, complete insulation is impossible. History teaches that technology tends to flow where there’s demand and loose regulations.

Yet proponents of the bans stress that letting China freely acquire AI chips might materially change the balance in everything from cyber-espionage to battlefield drones. Each side faces trade-offs: strict controls slow competitors but also forfeit some economic opportunity and might incentivize heavy-handed retaliations by China (such as buying more Japanese or European chips). Indeed, the tug-of-war is not one-sided. The U.S. and its allies, particularly in Asia and Europe, have been trying to erect a semiconductor “fence” around China, tightening not just export rules but also export enforcement. Singapore and Japan have joined broad multilateral measures, understanding the stakes.

For now, the inventive tactics — from suitcases of data to rented servers — reveal a cat-and-mouse game where policy and business ingenuity collide. Western tech observers watch closely: if Chinese companies can effectively train huge AI systems using American chips overseas, it may blunt the strategic edge the chip bans aimed to buy. In response, governments may escalate the restrictions. The cycle could continue until a new balance is found – possibly via global AI norms, tighter allied coordination, or breakthroughs in domestic Chinese technology that render the bans moot.

One thing is clear: in the high-stakes global AI race, raw data is as precious as chips. And if the rules say, “no chips allowed,” innovators are showing they’ll gladly carry the chips in their train of thought – by flying the data itself wherever the hardware resides.

Note: This is my own opinion and not the opinion of my employer, State Street, or any other organization. This is not a solicitation to buy or sell any stock. My team and I use a Large Language Model (LLM) aided workflow. This allows us to test 5-10 ideas and curate the best 2-4 a week for you to read. Rest easy that we fact check, edit, and reorganize the writing so that the output is more engaging, more reliable, and more informative than vanilla LLM output. We are always looking for feedback to improve this process.

Additionally, if you would like updates more frequently, follow us on x: https://x.com/cameronfen1. In addition, feel free to send me corrections, new ideas for articles, or anything else you think I would like: cameronfen at gmail dot com.

interesting times