Retaliation Politics: How South Africa’s HIV Research Got Caught in Trump’s Old Grudge

Spending Cuts Targeting Research and Financial Aid Could Result in Many Unnecessary Deaths

Related Articles: USAID cuts and DOGE, Big Beautiful Bill and Spending Cuts, and Benefits of Basic Research.

What if medical research is the new battlefield for international grudges? In South Africa, clinics and labs that once drew on American aid have suddenly run dry. In January 2025, a Trump administration order froze virtually all U.S. foreign aid – including billions to HIV and TB programs – and by February an executive order specifically cut funding to South Africa. This is more than a budget cut; it feels like score-settling over a political slight. In 2018, then-President Trump tweeted that white South African farmers were being “seized” and “killed” – an echo of the fringe “white genocide” trope – infuriating Pretoria. South African officials denounced the claim as “misinformed” and “divisive”, but a long memory may linger. Could today’s aid freeze be payback for 2018’s tweet? The answer has stark consequences: lives now depend on whether science can survive in the crossfire of geopolitics.

South Africa has some of the highest incidences of AIDS on the African continent. Source: Wikipedia

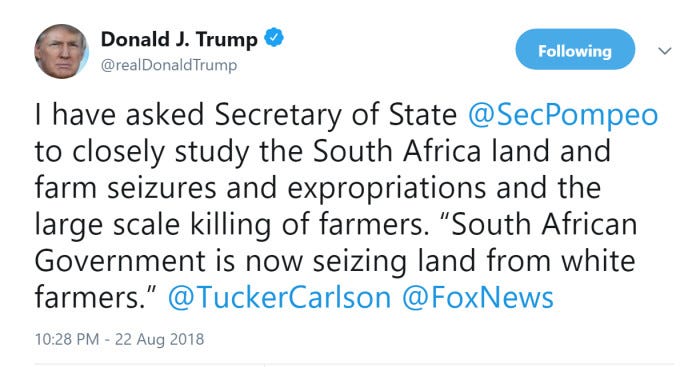

Diplomatic Flashpoint: 2018’s Tweet and the Rift It Caused

Trump’s Tweet arguing, without evidence, that the South African government is seizing land from white farmers. Source X.

It began with a tweet. In August 2018, President Trump reposted a Fox News segment claiming that South Africa was “now seizing land from white farmers” and urged Secretary of State Pompeo to “study land seizures & the large scale killing of farmers”. The incendiary post leaned on the fringe idea of “white genocide” in South Africa. Pretoria was furious. President Cyril Ramaphosa’s administration blasted the White House for relying on “false information” and “reminds us of our colonial past”. A South African spokesman warned the matter would be taken up through diplomatic channels. Even Julius Malema of the ruling ANC called Trump’s framing dangerous. Relations coolly endured, but few forgot the insult.

Fast-forward to 2025. In January, as Trump entered a second term, the White House issued a sweeping freeze on foreign assistance – PEPFAR HIV programs, USAID grants, NIH research partnerships – effective January 20, 2025. Within days, South African clinics serving the most vulnerable communities abruptly shuttered. By February 7, Trump signed a specific executive order targeting Pretoria, citing its land reform law and even its vote against Israel at the ICJ. The directive was blunt: stop all aid to South Africa. In his announcement, Trump accused South Africa of racial bias against white Afrikaners, echoing the theme of 2018. In other words, the very issues that sparked outrage six years earlier were now given formal sanction – with science caught in the middle.

Cutting the Lifelines: The Impact on Research and Public Health

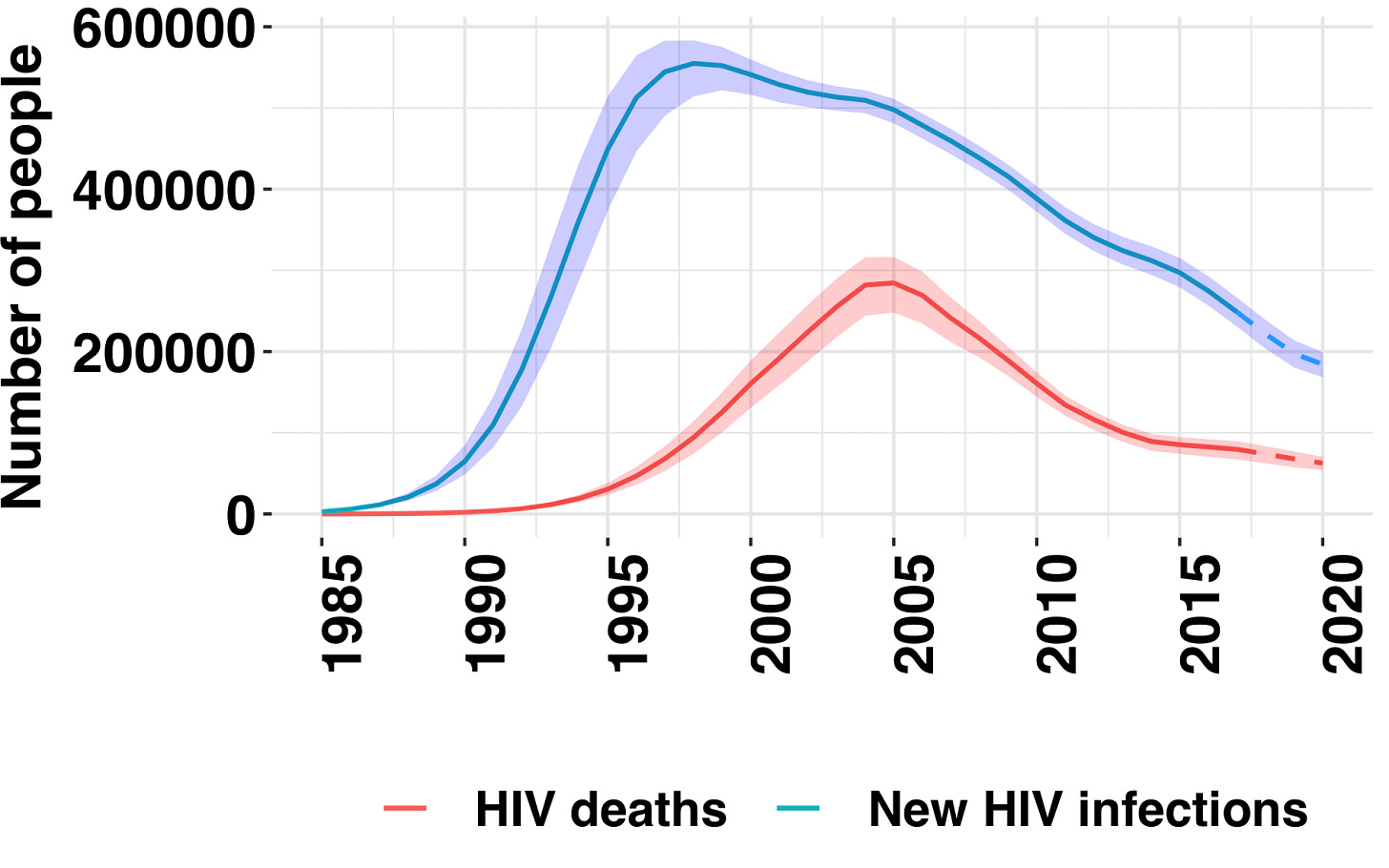

AIDS deaths and HIV infections in South Africa. Source: Spotlight

The freeze has real victims. In Johannesburg’s Hillbrow township, 62‑year‑old Lebo still remembers the day her HIV clinic was told to close. “I’m weak,” she said then, tears in her eyes. A charity dispensary for sex workers lost its U.S. funding and shut in January 2025. Lebo now pays 30% of her income for medication, and shudders at government clinics where sex workers are scorned. Her story is chillingly common. In January, Trump had ordered a 90‑day pause on foreign aid, including the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Within weeks, all clinics for “key populations” – sex workers, LGBT+ individuals, drug users – were closing. “With the USAID cuts, we can’t do these [support] programs anymore,” lamented social workers like Rebecca Chakane in Soweto as food vouchers and support groups were abruptly pulled away. Across the country, community NGOs saw vital programs evaporate. The Networking HIV and AIDS Community of Southern Africa (NACOSA) shut down every USAID-supported initiative; over 160 of its 470 staff were laid off immediately. Even basic care rooms for rape victims, which provided HIV prevention medication, went dark.

It’s not only community projects suffering. South Africa’s scientific research institutions are hemorrhaging. U.S. agencies – NIH, CDC, USAID, PEPFAR – have been major donors to clinical trials and labs across the country. In 2023 alone, South Africa received roughly $460 million in U.S. HIV aid (PEPFAR) – about 18% of its HIV budget. Health Policy Watch and civil society groups have crunched the numbers: at least 39 clinical research sites are now “under threat,” endangering 27 HIV trials and 20 TB trials. Add to that USAID-funded vaccine and diagnostics projects. Public Citizen found 32 USAID trials listed globally – South Africa was the single most common study site (9 trials) – involving tens of thousands of participants. Now dozens of trials have been paused mid-stream, and nearly 100,000 volunteers have seen their studies suspended.

As an example, Médecins Sans Frontières and the Treatment Action Group highlight a grim statistic: roughly 25 major U.S.-funded TB research sites once operated in South Africa, with 12 trials and 30% of all participants coming from the country. (Each TB patient in those trials represented an investment of around $12,000.) The freeze means those trials cannot recruit, follow up, or even analyze their results in SA. Researchers call this an “ethics nightmare.” Prof. Ian Sanne, head of an NIH-funded unit at the Wits University, noted that funds stopped immediately on Jan 24 with no wind-down – clinical staff were suddenly furloughed and treatment rings removed from patients without explanation. Professor Ntobeko Ntusi, head of the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), warns that “nearly a third of [the Medical Research Council’s] income” is from U.S. grants. He cries catastrophe: “South Africa is the biggest NIH recipient outside the U.S…. [I]f funding is stopped…[the] consequences will be catastrophic for science important to the whole world”.

At universities, funding losses are staggering. Analysts estimate NIH and CDC cuts could slash research budgets by 30% at major institutions. Wits University alone stands to lose an estimated $150–$180 million over the next few years. Departments are laying off staff, canceling PhD and clinical trials, and scrapping vaccine and microbicide research. “We were well on track to eliminate infant HIV,” says an American epidemiologist involved in a PEPFAR trial in South Africa. In the name of speeding cutbacks, projects that would take decades to complete are being terminated overnight.

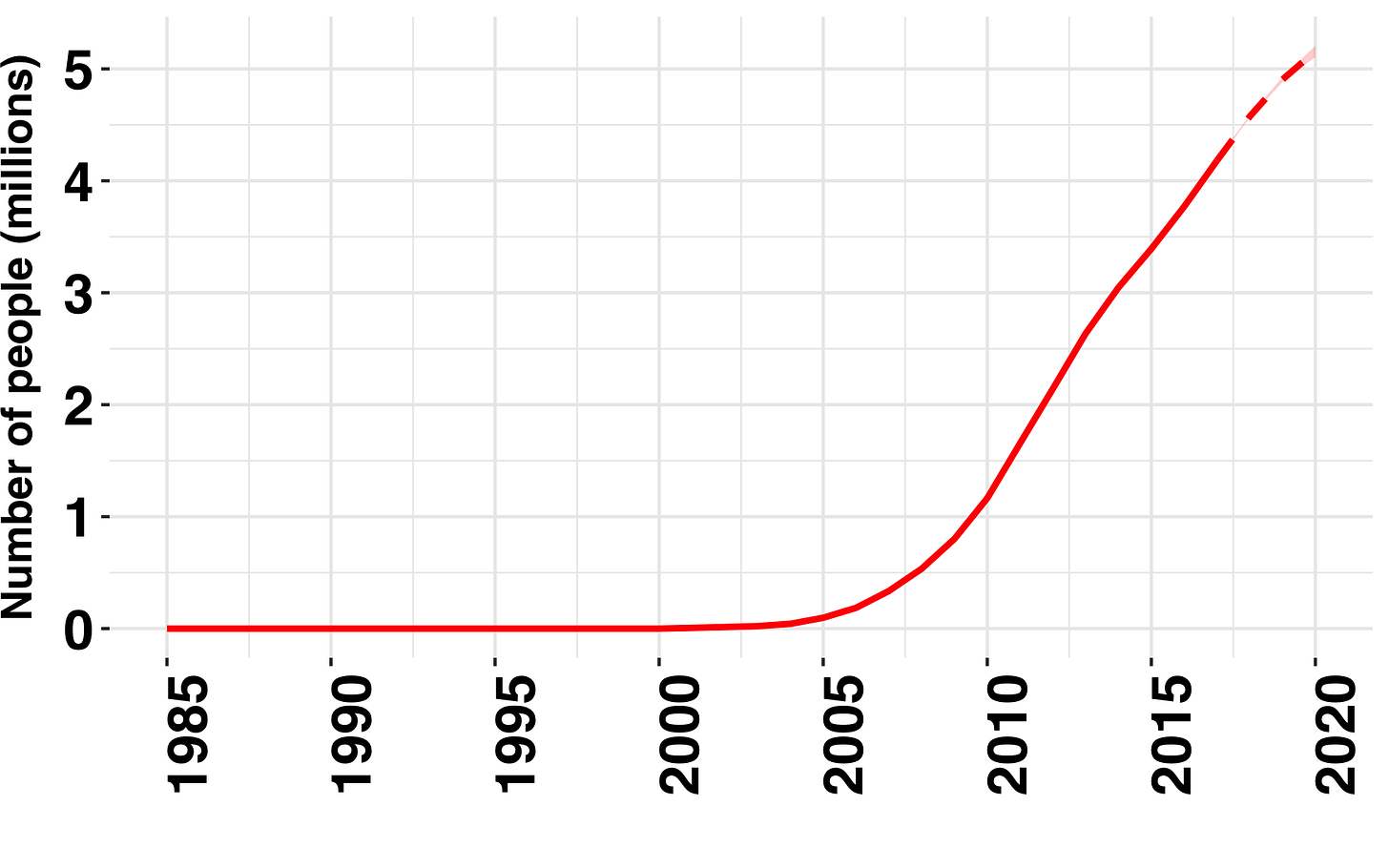

Antiviral treatment can permentantly prevent HIV from becoming worse/developing into AIDS. This treatment has been essential for South Africa and the aid cuts will threaten this progress. Source Spotlight.

This pain is acute for patients. Ramphelane Morewane of South Africa’s health department, who oversees the national AIDS program, calls the situation a “crisis”. Without outside aid, millions of HIV-positive South Africans – 12% of the population – might lose counseling, testing, and support, even if ARV drugs themselves are still purchased domestically. As one AIDS support worker put it, “What is at risk is the support we were giving to households of kids infected with HIV”. Already, data from SA clinics show viral suppression rates slipping and testing falling when PEPFAR support vanished. In short, decades of progress against HIV and TB – often achieved with American help – are being undone in a matter of months.

Target or Trend? Unpacking the Motives Behind the Cuts

Is this cutback a rogue vendetta or part of a broader shift in U.S. policy? The answer appears to be: both. On one hand, the timing and targeting are telling. In the span of weeks, the new administration delivered two blows: a general 90-day freeze of all foreign aid, and an explicit sanction on South Africa. The latter came via an EO on Feb 7, 2025, which unambiguously named Pretoria as an offender on race issues. Even some of the halted trials sensed it: one global study coordinator reported that colleagues were “worried” the stop-work order came from “an executive order directed specifically at South Africa”. In other words, researchers themselves see the cuts as politically chosen, not random belt-tightening.

Carnegie Endowment analysts agree: South Africa is being singled out. Their report notes that the USAID dismantling “particularly affected the PEPFAR program – a cornerstone of the U.S.-South Africa health partnership.” In 2023 alone, SA got ~$460 million from PEPFAR; freezing it “has led to job losses” and “could jeopardize efforts to combat one of the world’s most severe HIV epidemics”. A separate study noted that Trump’s February EO specifically faulted SA for discriminating against Afrikaners and quoted Pretoria’s expropriation law as just cause for sanctions. The optics are clear: the freeze feels punitive.

But at the same time, there is a broad pattern. Washington’s aid freeze isn’t limited to Africa. Within 5 months of taking office, the Trump administration announced a review of all foreign aid programs, and proposed rescinding billions (e.g. a $9.4 billion cut to foreign assistance is under Congressional consideration). U.S. science agencies are also feeling the squeeze: more than $30 billion across NASA, NSF and other programs is “on hold”. This suggests the administration is reorienting foreign and research spending globally.

In practice, however, science projects are hardly exempt from geopolitics. Even NIH research grants – technically “competitively awarded” – are being funneled through these edicts. As Dr. Marcus Low notes, “NIH funding is not aid; it’s competitive funding researchers here competed for”. That makes these cuts all the more jarring. It means top laboratories, built over decades of collaboration, can be shut down by a stroke of the executive pen. Indeed, one ongoing TB vaccine study already canceled its community outreach component after South African partners abruptly lost funding. In another recent case, American scientists discovered that a stop-work order halting grant payments violated both their contractual obligations and basic medical ethics – leaving sick trial participants stranded.

The experts warn of a chilling effect. As Linda‑Gail Bekker of Desmond Tutu HIV Centre observed, American and African scientists have co‑developed advances now used globally – like long‑acting HIV prevention shots and new TB drugs – precisely because of their partnership in SA trials. Cutting that ties undermines not just South African health, but future treatments worldwide. “We owe it to U.S. taxpayers and our participants to finish our studies,” one researcher wrote in dismay, lamenting the loss of trust in U.S. research governance. In sum, the dispute over land and history may be playing out on the backs of people in clinics and labs – a sobering lesson in how fragile scientific collaboration can be when geopolitics intrudes.

Global Consequences: A Precedent for Aid in the 21st Century

The fallout extends beyond one country. South Africa, after all, has the world’s largest HIV epidemic (7.7 million people living with HIV) and a top 10 TB burden. What happens here matters to global health. SAMRC’s Ntusi reminds us: “Many of the major trials that advanced our understanding of HIV and TB ... emanated from South Africa”. Indeed, long-acting PrEP and modern TB therapies owe their existence in part to SA research. If those pipelines dry up, so do future innovations – in the U.S. and beyond.

Already, international health agencies are sounding alarms. UNAIDS reports that “millions” depended on the abruptly paused U.S. aid for life-saving HIV treatment. The Stop TB Partnership estimates that just a few months of U.S. funding disruptions could cause tens of thousands of excess TB deaths – and by 2030, over 2.2 million more if cuts persist. These are not distant concerns: TB and HIV spread globally, and drug-resistant strains know no borders. U.S. policymakers have often said global health funding also protects Americans by stopping pandemics at their source. This episode suggests those protections are only as strong as the politics behind them.

What’s more, the U.S.–Africa relationship is in peril. The Carnegie analysis warns that alienating South Africa – a relatively stable democracy with important mineral wealth and the African Union’s chairmanship – weakens U.S. influence on the continent. If Washington’s credibility as a partner is damaged, China or Russia may fill the vacuum. On the South African side, government leaders face domestic strain: How to make up a loss equal to 17% of their HIV budget, or to find nearly 30% of SAMRC’s income? Already Pretoria is tapping reserves and domestic donors for urgent cash, but experts worry this is temporary.

In short, this episode serves as a warning. When medical research and public health programs become pawns in a political fight, nobody wins. Clinics close, patients suffer, and trust in aid and science erodes. The Atlantic Council’s Africa director argues that Africans might use this as a “wake-up call” toward self-reliance, but the immediate reality is stark: communities and scientists are left picking up the pieces of someone else’s feud. How long before another country’s grudge sidelines critical health efforts? The precedent is set, and it’s a dangerous one.

Notes: This is my own opinion and not the opinion of my employer, State Street, or any other organization. This is not a solicitation to buy or sell any stock. My team and I use a Large Language Model (LLM) aided workflow. This allows us to test 5-10 ideas and curate the best 2-4 a week for you to read. Rest easy that we fact-check, edit, and reorganize the writing so that the output is more engaging, more reliable, and more informative than vanilla LLM output. We are always looking for feedback to improve this process.

Additionally, if you would like updates more frequently, follow us on x: https://x.com/cameronfen1. In addition, feel free to send me corrections, new ideas for articles, or anything else you think I would like: cameronfen at gmail dot com.