Signs of Potential Fraud and Irregularities in Tesla’s Sales and Accounting

Note: If you are looking at other stock pitches, I wrote an analysis of St. Joe Co.

In March 2025, the Toronto Star broke the news that Transport Canada has launched an investigation into whether Tesla gamed a federal EV rebate program by falsely inflating end-of-month sales. In the final three days of Canada’s iZEV electric vehicle incentive (which provided a C$5,000 rebate per EV), four Tesla stores claimed to sell 8,653 vehicles, filing for C$43.1 million in rebates – more than half of the program’s remaining budget. To put this in perspective, Tesla reported selling more cars in those 3 days than in the entire first quarter of 2024 in Canada. One Quebec City Tesla location alone purportedly delivered over 4,000 vehicles in a single weekend, even though it could only physically stock a few hundred cars. Such volume in 72 hours is logistically implausible, and dealers allege many of these “sales” were paper transactions to grab rebates rather than genuine customer deliveries.

The consequence of Tesla’s rebate filings was immediate: the government’s EV rebate fund was depleted by the end of that weekend, leaving 2,295 other EV buyers without their promised rebates (non-Tesla dealers had already given the discount to customers and are now owed ~$10 million). The Spokesperson of the Canadian Automobile Dealers Association accused Tesla of “gaming the system,” noting “These (dealers) shouldn’t be left making a payment on behalf of the Government of Canada”. In response, Transport Canada officials called the reported figures “unacceptable” and are auditing Tesla’s rebate claims in detail. The central question is whether Tesla improperly booked sales before the rebate deadline – for example, delivering cars “on paper” or to itself – to qualify for incentives that would otherwise expire. Tesla has not publicly detailed how it achieved such a spike, but the investigation’s credibility is backed by multiple media reports and government confirmation that an inquiry is underway.

Context: If confirmed, the Canadian case would exemplify Tesla recognizing revenue and deliveries prematurely for financial gain. Recording a sale (and applying for a government rebate) requires that the vehicle is delivered to the end-customer. Filing thousands of rebate claims suggest Tesla reported those cars as delivered. However, if customers did not actually receive the cars by that date, Tesla may have violated revenue-recognition rules and committed subsidy fraud. The sheer scale – 8,600+ cars worth over C$40 million – and the fact that it occurred over a weekend (when government offices were closed) have raised serious credibility issues. Canadian authorities have even suspended further Tesla rebate payouts pending the investigation, and indicated Tesla may be barred from future incentive programs if wrongdoing is found.

Given this incident, I would like to further explore the shady business practices Tesla has engaged in.

Quarter-End Surges and Revenue Recognition Red Flags

Tesla’s business is known for its end-of-quarter delivery “pushes.” Each quarter, Tesla concentrates deliveries in the final weeks to meet targets and minimize inventory on its balance sheet. While it’s normal for businesses to try to hit quarterly goals, Tesla’s surges are unusually dramatic and have drawn scrutiny. Internal and external reports describe a “chaotic” rush to hand over keys before quarter-end, sometimes delivering cars with incomplete prep or encouraging customers to accept early delivery. This raises concerns about potential cutoff manipulation – e.g. recording revenue in Q4 for a car actually delivered in Q1 or offering buybacks/returns that effectively pull future sales into the present.

In fact, Tesla’s reported delivery numbers have shown inconsistencies around quarter boundaries. A 2019 analysis by MarketWatch noted that Tesla often releases preliminary production and delivery figures right after quarter-end, then updates them later in official filings – with figures frequently changing in those interim periods. For example, the full-year 2018 vehicle deliveries initially announced in a January 2019 press release were 320 units higher than the sum of quarterly deliveries Tesla had reported throughout 2018. Such adjustments might seem minor (a fraction of annual sales), but the pattern of revisions recurred multiple times and “raised questions about the quality of the company’s accounting function” and disclosure controls. In other words, observers wondered if Tesla’s rush to report positive numbers led to errors or aggressive counting that later had to be corrected – a potential red flag for weak internal controls.

Tesla’s inventory accounting also comes into play. By delivering as many cars as possible by each quarter’s last day, Tesla reports very low finished goods inventory relative to sales. However, analysts have pointed out that this practice could mask unsold stock or cancellations. In late 2016, Tesla even allegedly encouraged employees to buy cars (with full return rights) to boost delivery figures, essentially pulling forward sales – a tactic that, if true, would be highly questionable ethically. (Tesla’s CEO Elon Musk has publicly insisted such moves are against policy, saying “NEVER discount a new car... this is why I always pay full price”, in an email to staff. Nonetheless, reports of last-minute discounts and internal sales have surfaced in the past.)

Another area to watch is revenue recognition timing. Tesla’s accounting policy (as stated in its 10-K filings) is to recognize automotive revenue upon delivery to the customer. If Tesla marked those Canadian sales as delivered in January when they weren’t, it could constitute improper revenue timing. Improper timing of revenue recognition is one of the most common SEC enforcement issues in accounting fraud cases. While Tesla has not been charged by the SEC for revenue recognition fraud to date, the pressure to meet ambitious quarterly targets could create an incentive for borderline practices. Investors have drawn parallels to “channel stuffing”, where companies push inventory onto customers or intermediaries early. In Tesla’s case, direct sales mean there is no dealer to “stuff,” but the Canadian rebate episode suggests an analogous tactic: stuffing the channel with subsidized deals before a deadline, even if deliveries weren’t truly completed.

Inconsistencies in Financial Filings and Disclosures

Tesla’s official filings sometimes provide hints of these pressures. While Tesla’s auditors have never issued a restatement for improper sales accounting, there have been signals of aggressive accounting that attracted regulatory attention. Notably, in 2016 the U.S. SEC called out Tesla for using “individually tailored” non-GAAP financial metrics in its earnings releases. Tesla had been adding back certain costs and deferrals to show a more favorable revenue and profit picture. The SEC warned that Tesla’s adjustments (such as excluding the impact of its resale value guarantees on revenue) could mislead investors. Tesla ultimately adjusted its reporting practices, but the incident shows a willingness to push accounting boundaries.

More recently, Tesla’s warranty and repair accounting has been questioned. Warranty repairs are a normal cost for automakers, and GAAP requires accruing a reserve for expected warranty work. According to a whistleblower complaint in 2021, Tesla allegedly directed employees to miscategorize many repair costs as “goodwill” or non-warranty service to avoid drawing down its warranty reserve. By doing so, Tesla could understate its warranty expenses and liabilities, making its gross margins look better. The whistleblowers claimed this practice was pervasive, yet not visible to investors. (Under Sarbanes-Oxley, management must report any material weaknesses in internal controls; the whistleblowers argued that Tesla’s auditors, PwC, should have flagged a material weakness over these practices.) This specific allegation remains unproven – the SEC did not take enforcement action – but it aligns with a broader pattern of Tesla seemingly downplaying negative financial information. Indeed, Tesla’s auditor identified warranty accounting as a “critical audit matter,” suggesting it warranted special attention due to judgment or potential risk.

Another example of disclosure issues is Tesla’s vehicle delivery reporting. As mentioned, Tesla’s initial press releases and later 10-Q/K filings sometimes did not match. In 2019, observers noted that Tesla released multiple versions of its delivery numbers for the same quarter, updating the figures frequently. Such behavior is unusual – most automakers report once per quarter with minimal revisions. The MarketWatch report pointed out that this could signal weaknesses in Tesla’s accounting and disclosure controls, possibly due to high staff turnover in the finance department at the time. (Tesla went through several chief accounting officers and even had its Chief Financial Officer resign and return during that era.) Consistent, reliable reporting is an important hallmark of strong financial controls, so these inconsistencies were a yellow flag for analysts.

Past Incentive and Sales Controversies in Other Markets

The 2025 Canada situation is not the first time Tesla has been accused of gaming government incentive programs. In Germany (2017), Tesla faced similar accusations regarding the country’s EV subsidy. Germany offered a €4,000 rebate for electric cars under a certain base price. Initially, Tesla’s Model S was too expensive to qualify, so Tesla unbundled various features into a “Comfort Package” to lower the base price to just under the cap. In theory, this made a stripped-down Model S eligible for the rebate. However, an investigation by the German government (following an exposé by Auto-Bild magazine) found that Tesla’s base model was essentially a phantom – customers could not actually order a car without the bundled options, meaning all Tesla sales were above the price limit and technically ineligible for the subsidy. Auto-Bild bluntly labeled Tesla’s tactic a “deception”, even using words like “fraud” and “cheating” on its cover. In response, German authorities temporarily removed Tesla from the EV incentive program, and hundreds of customers were asked to repay their rebates. Tesla vehemently denied wrongdoing, insisting that any customer could buy the base version and that some actually had. Ultimately, Tesla agreed to cover the €4,000 rebates for affected buyers and was later reinstated to the program after demonstrating compliance. Still, the incident revealed Tesla’s willingness to exploit loopholes in incentive schemes and the resulting risk of regulatory backlash. It closely foreshadows the Canadian case: in both instances Tesla was accused of maximizing subsidy claims in ways not intended by the program.

Going back further, Tesla leveraged incentives in California in a contentious way as well. In 2013, Tesla famously held a press event demonstrating a battery swap technology for the Model S – swapping a depleted battery for a charged one in minutes. This demo wasn’t just tech showmanship; it had a financial motive. California’s Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) credit program at the time awarded extra credits to EVs that could refuel quickly, as a proxy for convenience on par with gasoline cars. By showing battery swapping was possible, Tesla’s Model S qualified for 7 ZEV credits per car instead of 4, and Tesla nearly doubled the credits it earned from its entire fleet with just that one demonstration. In practice, Tesla never rolled out a usable swap service to customers (the one pilot station saw little usage), leading critics to argue the swap was a sham designed solely to “steal” credits. One analysis estimated Tesla earned in the order of $100 million in extra credit revenue thanks to this strategy. While not illegal under the letter of the CARB rules then, it was widely viewed as against the spirit of the incentive program, to the point of being dubbed the “Tesla Battery Swap Fraud” in some press. This early episode set a precedent: Tesla learned how lucrative regulatory incentives can be – and showed creativity in securing them, arguably crossing ethical lines. The pattern repeated in Germany 2017 and now in Canada 2025, albeit each with different methods.

Regulatory Investigations and Whistleblower Allegations

Tesla’s aggressive practices have not escaped the notice of regulators and insiders, leading to several investigations and whistleblower tips over the years:

Department of Justice (2018) – The U.S. DOJ investigated whether Tesla misled investors about Model 3 production during its 2017 ramp-up. Specifically, prosecutors examined if Tesla made public production projections it knew it could not meet – for example, Elon Musk’s claim in mid-2017 that Tesla would be building 20,000 Model 3s per month by that December, when in fact only 2,685 were produced in all of 2017. Tesla acknowledged it received DOJ requests for information on this matter. Ultimately, no charges were announced from this probe, but it underscores that Tesla’s communication of sales/production figures has been considered borderline enough to trigger a federal inquiry. (Around the same time, the SEC also subpoenaed Tesla over Model 3 production forecasts, and a class-action lawsuit by shareholders alleged Tesla concealed production problems – though a judge later dismissed that suit.)

Whistleblower Martin Tripp (2018) – A former Tesla technician, Martin Tripp, turned whistleblower in mid-2018 and alleged serious production fraud at the Nevada Gigafactory. In a tip to the SEC, Tripp claimed Tesla was installing flawed battery modules in Model 3s and, crucially, overstating Model 3 production numbers by up to 44%. He provided vehicle identification numbers and internal documents that he said evidenced Tesla counting scrapped or reworked batteries as finished product. Tesla’s response was to sue Tripp for hacking and theft of data, and Musk labeled him a saboteur. Tripp’s claims, if true, suggest Tesla was padding its delivery and production figures during the difficult Model 3 ramp (potentially to prop up its stock price and meet targets). While the SEC’s reaction to Tripp’s tip isn’t public, no enforcement followed immediately. Tripp himself was eventually hit with a judgment to pay Tesla for damages, undermining his whistleblower retaliation case. Nonetheless, the allegations remain part of the mosaic of concern about Tesla overstating its operational achievements. It’s worth noting that Tripp’s claims dovetail with the DOJ inquiry above – both center on Tesla possibly saying it was making more Model 3s than it really was in 2017–2018.

Whistleblower Complaint (2021) – In 2021, a Tesla insider (Lukasz K.) and an outside researcher filed a detailed complaint to the SEC, alleging Tesla “may have violated securities laws and flouted accounting standards.” This complaint, revealed in 2023, catalogued numerous potential irregularities. Among the claims: Tesla was pervasively misclassifying expenses, as mentioned (hiding warranty costs), and possibly recognizing revenue prematurely for vehicles or services. The SEC reportedly only examined one portion of the complaint and then closed the case without interviewing the whistleblowers. The whistleblowers, frustrated by the lack of action, later leaked a trove of internal documents (“Tesla Files”) to the media in Germany. While much of the leaked info related to technical and customer data, the very existence of an 18,000-document archive suggests these individuals had substantial evidence. The fact that Tesla’s former CFO Zach Kirkhorn resigned abruptly in 2023 with no clear explanation also fueled speculation – including by analysts like Dan Ives of Wedbush – that there “may have been disagreements over some aspect of Tesla’s financial strategy or reporting”. This is speculative, but it occurred on the heels of the whistleblower revelations, leading some to connect dots about potential internal dissent on accounting practices.

Other Ongoing Probes – Tesla is also facing a criminal investigation by the DOJ (as of 2022) into its Autopilot/FSD marketing claims. Although this is more about consumer deception (safety promises) than financial fraud, it reinforces a pattern of scrutiny on Tesla’s truthfulness. In addition, Tesla’s solar panel division came under SEC investigation in 2019–2020 after a fire risk whistleblower complaint (Tesla eventually disclosed certain issues and settled some customer claims). Combined, these instances show Tesla has been subject to an unusually broad array of probes, from accounting and production claims to product-related representations.

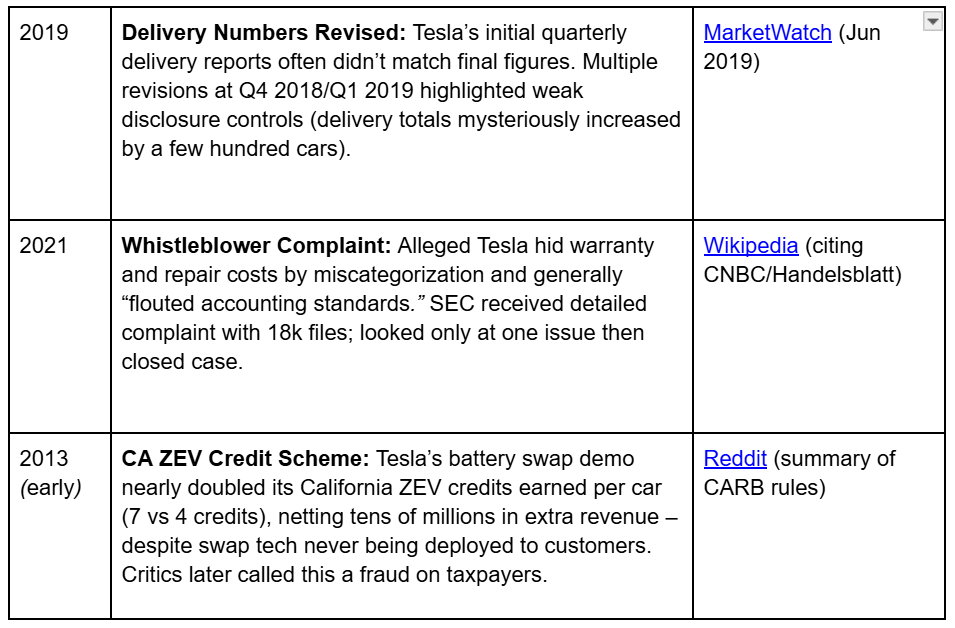

Table 1 below summarizes several noteworthy findings and allegations over the years, with dates, the nature of the concern, and sources:

Conclusion

From North America to Europe, Tesla has repeatedly been accused of stretching the truth in service of its growth narrative. The Canadian case in 2025, where Tesla allegedly staged an unprecedented sales spike to harvest government rebates, is only the latest instance raising eyebrows. Historical patterns – such as end-of-quarter delivery rushes, inconsistencies in reported numbers, and creative exploitation of incentive programs – provide important context. In several instances (Germany’s subsidy program, California’s ZEV credits, etc.), Tesla’s tactics stayed just within legal lines while violating the intent of the rules, prompting authorities to tighten or revisit those rules. In other instances (Canadian rebates, alleged inflated deliveries), investigations are ongoing or allegations unresolved, leaving questions about whether Tesla crossed into outright fraud.

What is clear is that Tesla’s rapid rise has not been free of controversy. The company operates in a high-pressure environment set by Elon Musk’s bold targets, which may foster a culture of hitting the numbers by any means necessary. While Tesla’s innovative products and business model get much attention, regulators and analysts are increasingly focusing on its less glamorous bookkeeping and sales practices. The recurring nature of these red flags – over multiple years and jurisdictions – suggests that investors and regulators will continue to scrutinize Tesla’s quarterly reports and incentive program dealings for any signs of misconduct. As of this writing, the outcome of the Canadian investigation and other probes will be critical in determining whether Tesla merely pushes hard against boundaries or has indeed crossed the line into fraudulent behavior. The pattern of evidence and allegations outlined above provides a framework to judge new developments as they unfold.

Note: This is not a solicitation to buy or sell any stock. Feel free to send me corrections, new ideas for articles, or anything else you think I would like: cameronfen at gmail dot com.

If you are interested in listening to a (AI distilled) podcast on this article instead of reading, some of my articles will be posted as podcasts https://www.youtube.com/@cameronfen203. Unlike the articles, I have not listened to and fact-checked the podcast output. AI models are known to hallucinate information and even if it’s based on something factual, I encourage you to approach the podcast as entertainment and keep a skeptical eye out for fake news. Please like and subscribe here and on the youtube if you feel like it’s a worthwhile resource, as it helps other people find the blog. Let me know if you want more articles uploaded as podcasts.