Ibrahim Traoré: The Soldier-Turned-Leader of Burkina Faso

How a Small Time Captain Became Dictator of Burkina Faso

Related Articles: Cuts to South Africa's HIV Research and Trump’s Travel Ban.

Traoré and Putin. Source: Wikipedia.

A Captain’s Audacious Arrival:

One of the most popular names in Africa and the black diaspora currently is Captain Ibrahim Traoré, the current military leader and interim president of Burkina Faso. Once a quiet soldier from the country’s outskirts, Traoré has risen from being an unknown figure to becoming the world’s youngest military head in a dramatic coup that occurred on September 30, 2022. On October 3, 2022, the boyish face of the young leader emerged from the turret of an armored vehicle to the cheering of a crowd after arriving in the capital, Ouagadougou, with a heavily armed convoy. Dressed in fatigues with a trademark red beret, the 34-year-old flashed a smile and gave a thumbs-up to jubilant onlookers – some even waving Russian flags in approval.

Just days prior, Traoré had been commanding an artillery unit in Burkina Faso’s hinterlands; now he was being hailed as a liberator after spearheading the country’s second coup in eight months. This dramatic ascent from obscurity to adulation highlights the bold, populist leadership style that has defined Traoré’s rule: he appears fearless in the face of chaos and eager to cast himself as a champion of the people’s will. But who is Ibrahim Traoré, and how did this young officer capture power and the imagination of so many? The following report provides a detailed biography of Traoré – from his humble beginnings and military career to his sudden rise in 2022 – and analyzes his leadership style, policies, foreign alliances, and the controversies that shadow his tenure.

Early Life and Military Beginnings

A picture showing the location of Kéra (red tack) in relation to Ouagadougou and most of Burkina Faso. Source: Google Maps.

Ibrahim Traoré was born in 1988 in the small town of Kéra in Bondokuy, western Burkina Faso. Raised in a modest family, he was described by former classmates as a quiet yet talented student. Traoré pursued higher education at the University of Ouagadougou, where he studied geology and was active in student associations – notably the Association of Muslim Students and the Marxist-leaning National Association of Burkinabé Students (ANEB). This mix of religious faith and leftist activism hinted at the blend of values – social justice, patriotism, and Pan-Africanism – that would later color his political rhetoric. He graduated with honors in 2009, but instead of a civilian career, the 21-year-old chose the path of a soldier.

Traoré enlisted in the Burkina Faso army in 2009, embarking on a rapid military rise. Impressing his superiors early on, he was selected for specialized training in Morocco in air-defense tactics. By 2014, he had earned the rank of lieutenant, and four years later he gained valuable combat experience on a United Nations peacekeeping deployment in Mali. Serving in northern Mali at the height of an Islamist insurgency, Lt. Traoré saw action on the front lines. He participated in several counter-insurgency operations against jihadist militants and Tuareg rebels, reportedly showing considerable bravery under fire. His courage and composure earned commendations from commanders, burnishing his reputation as a capable young officer.

By 2019, Traoré was back on home soil, stationed in Burkina Faso’s volatile northern regions as the country’s own Islamist insurgency intensified. Promoted to Captain in 2020, he took charge of an artillery regiment and became deeply involved in Burkina Faso’s fight against militants linked to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group. These years in the field hardened Traoré and his cohort of junior officers, as they witnessed first-hand the toll of a conflict that had spread across northern and eastern Burkina Faso. Villages were emptied by jihadist attacks, thousands of civilians were killed, and the army suffered growing casualties and setbacks. This grim reality on the ground planted seeds of discontent in many officers, including Traoré, toward the country’s political leadership in the capital.

Rising Discontent in a Nation Under Siege

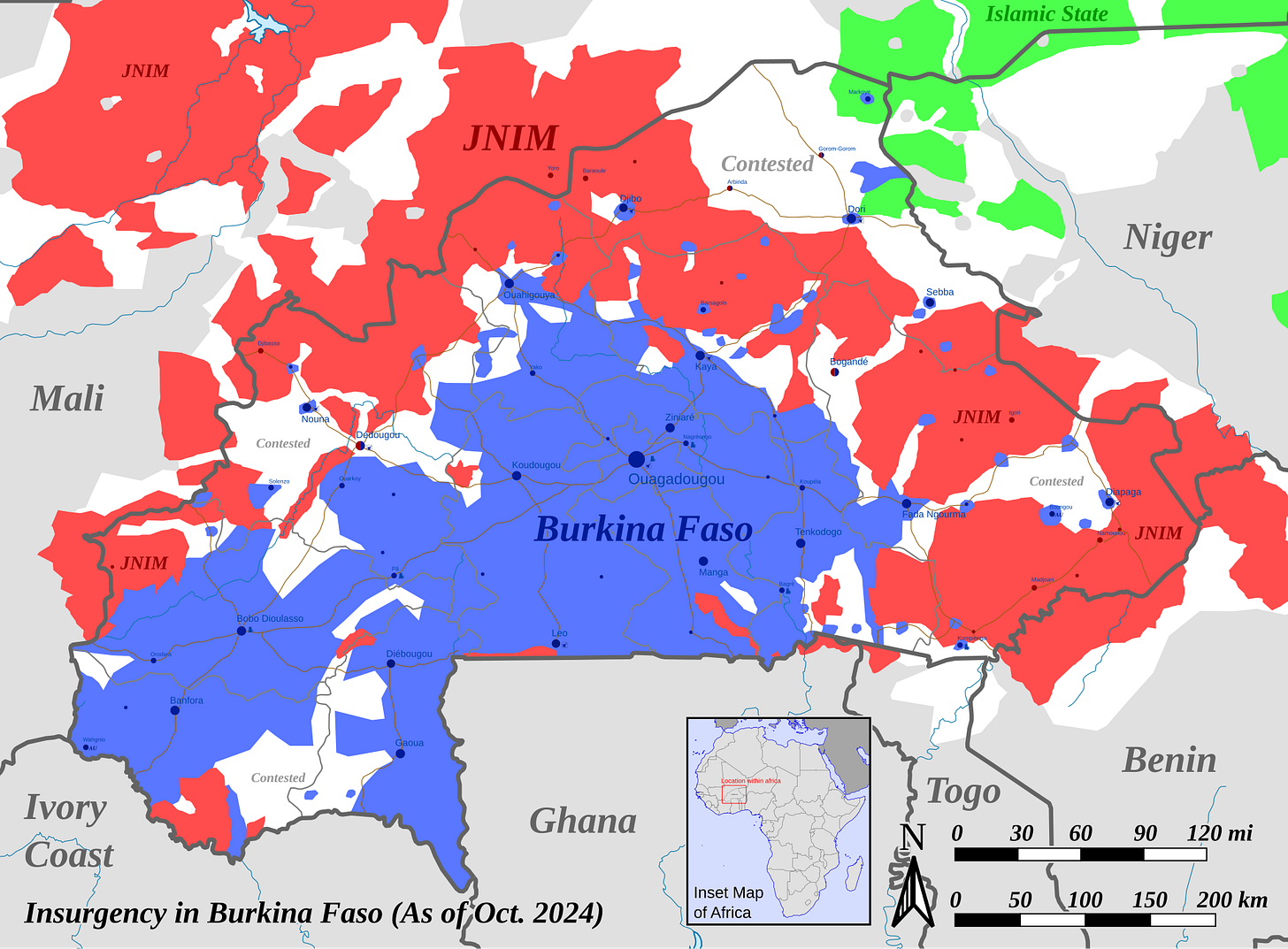

By early 2022, Burkina Faso was engulfed in crisis. A jihadist insurgency that began in 2015 had escalated into a nationwide emergency, with roughly 40% of the country’s territory outside government control and nearly two million people displaced from their homes. Front-line troops grew increasingly frustrated with what they saw as the government’s ineffectual response. Reports emerged of soldiers in remote outposts lacking adequate supplies, receiving irregular pay, and feeling abandoned by senior leadership. Morale was low, and anger at the civilian government of President Roch Marc Kaboré was mounting within the ranks.

The above chart shows much of Burkina Faso under the control of terrorists: Blue indicates government control, red—Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM)—an Al-Qaeda affiliated group, and green—Islamic State Sahel Province—an Islamic State (ISIS) affiliated group. Source: Wikipedia.

In January 2022, a group of military officers – led by Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba – mutinied and seized power, overthrowing President Kaboré. Damiba justified his coup by accusing the civilian authorities of failing to contain the Islamist threat. Many in the military, Captain Traoré included, initially welcomed Damiba’s takeover, hoping that one of their own could turn the tide against the insurgency. Traoré briefly served under the new junta, which named itself the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (MPSR).

Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba. Source: VOA.

However, it did not take long for the soldiers’ patience with President Damiba to wear thin. Despite the coup’s promises, militant attacks continued – and in some areas, even worsened. Critics said Damiba and his circle became preoccupied with politics in the capital while failing to make substantive changes on the battlefield. Notably, Damiba was slow to reform the army leadership or improve support for units in the field. By mid-2022, Jihadist raids and massacres of civilians were still occurring with alarming frequency, fueling public outrage. In late September 2022, a particularly deadly incident became the final straw: eleven Burkinabè soldiers were ambushed and killed by insurgents in the north, and a convoy of civilian resupply trucks was torched, leaving dozens of civilians dead or missing. This setback underscored that little had changed under Damiba’s watch.

Captain Traoré, who by then commanded an artillery unit in the northern town of Kaya, reportedly began voicing open criticism of Damiba’s “unproductive strategies” against the jihadists. Sensing growing support among junior officers and rank-and-file troops, Traoré and a cadre of fellow captains and lieutenants decided to act. Their grievances were not only about the persistent insecurity; they also resented what they saw as Damiba’s elitism and drift away from the rank-and-file. As one account later noted, Traoré had “slowly and quietly” grown disillusioned with his former comrade’s leadership, concluding that Damiba’s counter-insurgency approach was yielding “no tangible results”.

The September 2022 Coup – Seizing Power in Ouagadougou

On 30 September 2022, Ibrahim Traoré and his allies launched a lightning coup in the capital, Ouagadougou. Gunfire erupted around the presidential palace and the state television headquarters as mutinous soldiers moved in. By evening, 34-year-old Traoré had announced on national TV that the government was dissolved, the constitution suspended, and President Damiba removed from power. It was Burkina Faso’s second coup that year – a stunning development even in a region recently plagued by military takeovers. Traoré justified his putsch by citing the very reasons Damiba had given eight months earlier: the continuing failure to stop the “hordes of terrorists” marauding through the countryside. The young captain accused his predecessor of betraying the army’s trust, claiming Damiba had squandered time on “political maneuvers” instead of focusing on security. In a communiqué, Traoré and the insurgent officers charged that “the deteriorating security situation” required new leadership, and they vowed to fight the jihadists with renewed vigor.

Damiba initially refused to step down, sparking a tense standoff. For two days, gun battles between factions loyal to Damiba and Traoré raged in parts of Ouagadougou. There were also violent street protests: crowds attacked the French Embassy after rumors spread that France was hiding the ousted Damiba at a military base – claims that France and Damiba both denied. Some protesters vented their anger by waving Russian tricolors and chanting pro-Russian slogans, symbolically scorning France (Burkina Faso’s former colonial power) and welcoming a potential new partnership with Moscow. Amid the chaos, Traoré’s team appealed for calm and urged an end to vandalism, even as they leveraged the moment to signal a geopolitical shift. “The situation is under control and order is being restored,” an officer declared on TV, cautioning citizens to refrain from attacking French interests while pointedly noting that “many soldiers” sought “new partners” in the fight against terrorism.

Under pressure and via mediation by traditional and religious leaders, Lt. Col. Damiba agreed to resign on October 2, 2022, in exchange for guarantees of his security and certain conditions – including a promise by the coup leaders to uphold the January 2022 agreement to hold elections by 2024. Damiba fled into exile (initially to Togo), and the capital fell silent as Captain Traoré firmly assumed the reins of power. The coup was met with scenes of celebration by many civilians in Ouagadougou: Traoré was literally paraded through the streets atop an armored vehicle, greeted by crowds chanting his name and singing patriotic songs. The striking image of the baby-faced captain surrounded by ecstatic supporters, in a country where the median age is just 17, instantly cemented Traoré’s status as a folk hero to a frustrated populace.

On 21 October 2022, Ibrahim Traoré was formally sworn in as Burkina Faso’s transitional president, solidifying his position as head of state. During a ceremony in Ouagadougou under heavy security, the new leader – clad in military fatigues and a scarf bearing the national colors – took the oath of office. He pledged “to preserve and defend” the nation’s constitution and transitional charter, and outlined his interim government’s chief objective: “the reconquest of territory occupied by these terrorists”, as he bluntly put it. Acknowledging a “security and humanitarian crisis without precedent” in Burkinabè history, Traoré vowed to “win back our territory and dignity” from jihadist insurgents.

Crucially, Traoré also promised that his tenure would be short. The transitional charter adopted by his junta set a 21-month timeline for a return to constitutional order, with new elections envisaged for July 2024. “We did not come to continue [in power],” Traoré insisted in a radio interview days after the coup, emphasizing that an interim civilian or other president would be appointed to steer the country back to democracy. He presented himself less as a new strongman and more as a reluctant patriot stepping in to save the nation from collapse. “All that matters,” Traoré said, “is the fight [for security] and development. We will not be here for long.” These assurances were designed to mollify regional pressure – the West African bloc ECOWAS had a strict anti-coup stance – and to reassure Burkinabè citizens that the military takeover was a temporary rescue mission rather than a power grab.

Leadership Style and Pan-African Persona

From the outset of his rule, Ibrahim Traoré has cultivated a distinct leadership style and public persona that differentiate him from his predecessors. At 37 (as of 2025), he is the world’s youngest head of state, and he leans heavily into that youth appeal. Traoré projects the image of a charismatic yet no-nonsense soldier, often appearing in public wearing his combat uniform instead of civilian suits. He speaks in a frank, unvarnished manner, appealing to ordinary people’s patriotism and frustrations. Many in Burkina Faso and across Africa have been drawn to Traoré’s style, seeing in him echoes of Thomas Sankara – Burkina Faso’s iconic Marxist-revolutionary leader of the 1980s. Like Sankara (who took power at age 33), Traoré employs fiery pan-Africanist rhetoric and emphasizes national sovereignty. A senior researcher at global consultancy firm Control Risks observed that “Traoré’s impact is huge”, resonating far beyond his country, because “his messages reflect the age we are living in, when many Africans are questioning the relationship with the West”. In the eyes of admirers, Traoré has positioned himself as a symbol of a new generation rising up to demand dignity and self-determination for Africa.

Thomas Sankara. Source: Progressive International.

One defining moment for Traoré’s international image came at the Russia-Africa Summit in July 2023. Speaking before dozens of African heads of state – many his senior – Capt. Traoré caused a stir by bluntly admonishing them to “stop behaving like puppets who dance every time the imperialists pull the strings.” The remark, clearly aimed at Western powers and the legacy of neo-colonial influence, was widely publicized. Russian media amplified Traoré’s speech as evidence of Africa “waking up” to support Moscow’s stance, and pro-Traoré messaging flooded social networks. Indeed, Traoré has proven adept at leveraging social media to burnish his revolutionary credentials. Within months of taking power, a wave of online content – from slick videos to viral memes – portrayed him as a fearless anti-imperialist. Some of this content was misleading or even outright fabricated (including AI-generated videos falsely depicting Western celebrities praising him), but it helped fuel a “digital cult” of personality around Traoré. Even beyond Burkina Faso, he gained fans among pan-Africanist youth and members of the African diaspora who viewed him as a beacon of resistance against foreign domination. “Everyone who has experienced racism, colonialism and slavery can relate to his messages,” observed one analyst of his growing global appeal.

At home, Traoré’s personal style is often described as pragmatic and approachable, yet authoritative. Unlike some leaders, he has kept his private life intensely guarded – his wife and any children (if they exist) have never been presented publicly. He instead directs public attention to his work. Traoré is frequently shown visiting military barracks or front-line positions to boost troop morale, trying to send the message that he “leads from the front.” In one notable instance, Burkinabè media reported on his surprise visit to the embattled northern town of Djibo in late 2022, where he met with soldiers and civilians trapped by a jihadist blockade. Such appearances bolster his image as a hands-on leader who is unafraid to share hardships with ordinary people. Symbolism is also part of his repertoire: Traoré has become known for greeting people with an “iconic fist bump” in lieu of handshakes – a gesture that conveys solidarity and equality – and he references Burkina Faso’s revolutionary history (for example, invoking Sankara’s slogan “Fatherland or death, we shall overcome!” in speeches) to inspire unity.

Yet, for all the crafted heroism, Traoré’s leadership is also highly militaristic and single-minded. Observers note that he focuses almost obsessively on the security crisis above all else and tends to frame challenges in military terms. A comparison of styles noted that unlike the ideologically-driven Sankara, “Traoré’s leadership style is pragmatic and military-oriented, reflecting his background”. He has little tolerance for dissent (as later sections will detail) and often speaks in the language of urgency and war. This approach has won him followers who are desperate for decisive action. “He knows the art of politics – how to make a nation completely traumatized by war feel there is a better future,” one regional expert told the BBC, adding that Traoré is “really good at that game.” By tapping into popular anger at both the jihadists and foreign powers, Traoré has managed to rally a broad base of support, especially among young people who see their own frustrations and hopes reflected in his words.

Key Policies and Governance under Traoré

Since taking office as transitional president, Ibrahim Traoré has implemented a series of policies and initiatives that underscore his priorities. His governance has been characterized by an aggressive focus on security, a realignment of foreign partnerships, and populist economic measures aimed at asserting national control over resources. Below are some of the key policies and actions that have defined Traoré’s administration:

● “General Mobilization” Against Insurgents: Traoré’s first and foremost priority has been fighting the Islamist insurgency. Within weeks of the coup, he declared a nationwide state of emergency and launched a mass recruitment drive for the army and civilian auxiliaries. In October 2022, the junta announced plans to recruit 50,000 civilian volunteers as local defense fighters to aid the military. These volunteers, officially known as Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP), receive brief training and arms to protect their own villages alongside regular soldiers. By doubling down on arming local communities, Traoré aimed to “bring the war to the terrorists” in remote areas that the national army struggled to cover. The policy significantly expanded the security forces’ footprint and was popular among communities desperate for protection. However, rights groups warned that arming civilians en masse risked exacerbating ethnic tensions and abuses (a concern borne out by subsequent reports of VDP involvement in atrocities). Traoré has nonetheless championed the mobilization as a necessary “people’s war” to reclaim Burkina Faso’s territory.

● Army Reform and Leadership Purge: To address criticisms of the military’s performance, Traoré undertook changes in the army’s hierarchy. He removed several senior officers considered too close to the previous regime and promoted younger commanders seen as more aggressive against militants. The army chief of staff was replaced, and counterinsurgency operations were restructured under a new central command. Traoré also sought to improve soldiers’ conditions by streamlining pay delivery and procurement of arms. These steps were meant to reinvigorate the fighting spirit of the armed forces, which had been demoralized by years of heavy losses. It’s worth noting that even some of Traoré’s critics acknowledge a rise in army activity and offensives since he took charge, though the overall impact on security remains debatable (insurgent attacks have continued, if not increased, in some regions).

● Economic Nationalism and Resource Control: Echoing the revolutionary ethos of Burkina Faso’s past, Traoré has pursued assertive economic policies to assert national control over strategic resources – particularly gold, the country’s most valuable export. In early 2023, his government created a new state-owned mining company and mandated that all foreign mining firms give the state a 15% ownership stake in their Burkina Faso operations. Additionally, mining companies are now required to “transfer skills” to Burkinabè staff as part of their license agreements. These measures aim to ensure that more of the country’s gold profits stay in local hands. Traoré has framed this as part of a broader economic “revolution” to free Burkina Faso from exploitation and neo-colonialism. Under his watch, the junta has also embarked on building the nation’s first industrial gold refinery and establishing official gold reserves – initiatives touted as steps to financial sovereignty. In practice, Western mining companies have felt the squeeze: in late 2024, an Australian miner filed for international arbitration after Burkina Faso withdrew one of its exploration licenses amid these new rules. The government has likewise nationalized at least two gold mines previously owned by foreign firms and signaled intentions to take control of others. Such aggressive moves have unnerved some investors, but they have bolstered Traoré’s popular image as a defender of national wealth. “As part of what Traoré calls a ‘revolution’ to ensure Burkina Faso benefits from its mineral wealth,” reported BBC, the junta is unapologetically reshaping the mining sector in favor of the state.

● Diplomatic Realignment (France Out, Russia In): Perhaps the most consequential shifts under Traoré have come in foreign policy. He wasted little time in upending Burkina Faso’s traditional alliances. By early 2023, Traoré’s government moved to cut military ties with France, the country’s former colonial ruler. In January 2023, Ouagadougou formally terminated a defense agreement with France and demanded all French troops leave Burkina Faso within one month. At the time, around 400 French Special Forces were based near the capital to assist in counter-terrorism; they withdrew completely by February 2023, marked by a flag-lowering ceremony that ended France’s military operations on Burkinabè soil. Traoré also expelled France’s ambassador amid the frayed relations, accusing Paris of meddling and citing a public “wish for the country to defend itself” without outside interference. These steps were celebrated by Traoré’s supporters, who saw France’s presence as ineffective at best and neo-colonial at worst. In tandem, Traoré pivoted Burkina Faso toward Russia as a new strategic partner. He has publicly and repeatedly praised Russia’s support and ideology, and welcomed what he terms “new partners” in the fight against terrorism. Although Burkina Faso has not officially confirmed the presence of Russia’s Wagner Group mercenaries on its territory, Russian military advisors or trainers are believed to have been invited, mirroring the path taken by neighboring Mali. Notably, Yevgeny Prigozhin, the founder of Wagner, congratulated Traoré after the coup and declared his “full support” for the young leader, calling him “a truly worthy and courageous son of his motherland.” Under Traoré, government discourse shifted to outright hostility toward French influence and warm overtures to Moscow – a realignment that has profound implications for the region’s geopolitics. By late 2023, Burkina Faso joined hands with Mali (which had expelled French troops and embraced Wagner) and coup-hit Niger to form the “Alliance of Sahel States” (AES) – a new trilateral pact pledging mutual defense and cooperation in defiance of Western pressure. This alliance, born after Niger’s July 2023 coup, effectively created an anti-ECOWAS, pro-Russia bloc in the heart of West Africa.

● Sovereignty and Defiance of International Institutions: In line with Traoré’s nationalist bent, his administration has taken a combative stance toward international institutions when they are deemed to infringe on Burkina Faso’s sovereignty. In December 2022, for example, the junta expelled the United Nations’ Resident Coordinator (the top UN official in the country), alleging that she had painted an unjustly dire picture of Burkina Faso’s security situation and meddled in its affairs. The United Nations protested, saying there was “no grounds” for declaring the seasoned diplomat persona non grata, but the message from Traoré’s government was clear: it would not hesitate to kick out even long-term partners if they were perceived as impediments to its agenda. Similarly, Traoré’s Burkina Faso has shown solidarity with Mali and others in rejecting pressure from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). ECOWAS suspended Burkina Faso’s membership after the coups, but beyond rhetoric, it took little concrete action against Traoré’s regime – a fact perhaps attributable to the junta’s firm stance that external dictates (such as swift election deadlines) would not be prioritized over domestic security needs. In 2023, when ECOWAS threatened possible military intervention to reverse a coup in Niger, Burkina Faso (along with Mali) pointedly warned that such an intervention would be considered a “declaration of war” against them as well – a stark ultimatum that helped dissuade regional force and underscored Traoré’s readiness to defy his neighbors in the name of anti-imperial solidarity.

In summary, Traoré’s policy approach has been bold and often uncompromising. Whether in security, economics, or diplomacy, he has consistently favored radical measures that break with the past, even at the cost of isolating Burkina Faso from traditional allies. This approach has won him applause from those who long for a clean break from failed old policies. However, it has also set the stage for significant controversies and challenges that have increasingly come to the fore as his tenure lengthens.

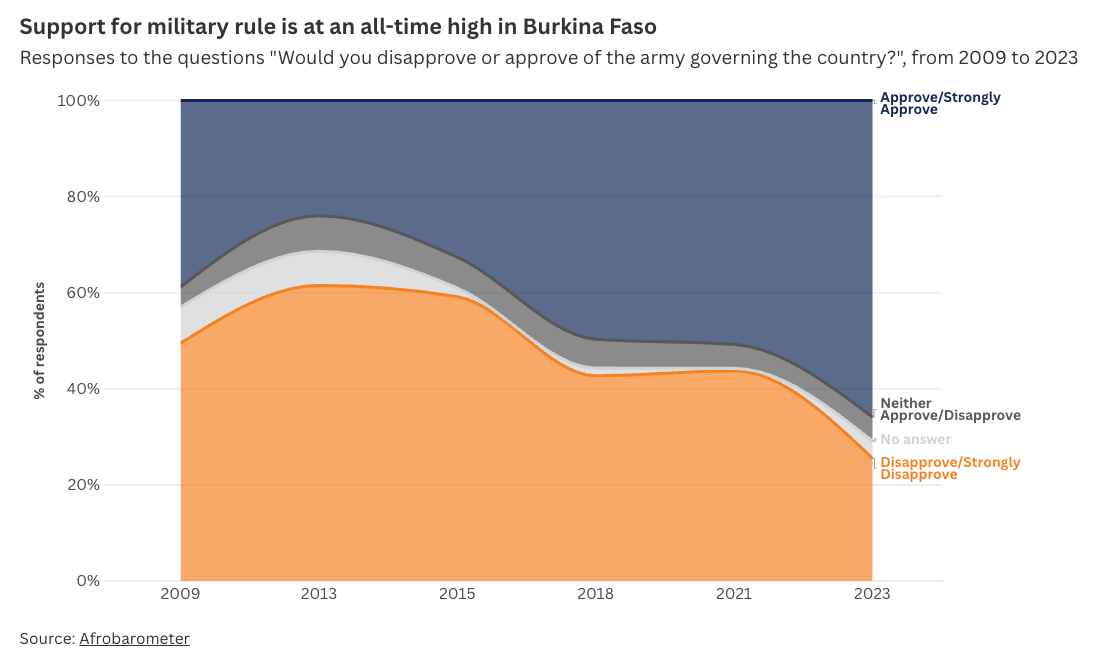

Popularity for a Traoré-style military government in Burkina Faso. Source: ISS Africa.

Controversies and Criticisms

While Captain Traoré enjoys a notable following at home and among pan-Africanist circles, his rule has been marred by serious controversies and growing criticism. Observers question whether the young leader’s actions match his revolutionary rhetoric, and whether Burkina Faso is better or worse off under his hardline leadership. Below, we examine the most significant controversies and challenges Traoré has faced since 2022:

● Escalating Insecurity and Unfulfilled Promises: The very issue that catapulted Traoré to power – the jihadist insurgency – remains unresolved. In fact, by many indicators the security situation has continued to deteriorate. Traoré originally promised to markedly improve security within “two to three months” of taking charge, yet over two years later, Islamist militants still launch frequent attacks across Burkina Faso. He has failed to fulfill his pledge to quell the decade-long insurgency, which has now entrenched itself and even spread into once-peaceful neighboring countries like Benin. Large swaths of rural Burkina Faso remain conflict zones, and the humanitarian crisis has deepened (with over 2 million displaced). Traoré’s supporters argue that he inherited a very difficult war and has at least increased the army’s tempo, but critics note that no clear victory is in sight. In essence, the core rationale for his coup – delivering better security than his predecessor – is increasingly in doubt.

● Crackdown on Dissent and Media Freedom: From early in his rule, Traoré’s junta has displayed an authoritarian streak, clamping down on political opposition, civil society, and press freedom. The transitional government indefinitely suspended the constitution and dissolved the legislature, meaning no institutional checks on executive power. Opposition politicians have been silenced or intimidated (some fled into exile), and public demonstrations against the junta have been banned under security pretexts. Perhaps the most striking has been the systematic repression of journalists and the media. The junta has banned French broadcasters like RFI and France24 from the airwaves, raided local media offices, and arrested reporters critical of the regime. In March 2025, authorities arbitrarily arrested three prominent journalists – the leaders of the national journalists’ association and a television reporter – after they spoke out about mounting censorship. The three were held at undisclosed locations, prompting fears of enforced disappearance. Human Rights Watch and other groups report that Traoré’s government has even used a draconian “emergency measures” law to conscript its critics into the military as a form of punishment. For example, journalists, civil society activists, and even magistrates who voice dissent have been forcibly sent to serve in front-line units as privates – an extreme tactic aimed at both silencing and intimidating would-be critics. Such measures have created a climate of fear domestically. The space for free expression and debate has virtually disappeared, drawing condemnation from press freedom organizations and democracies abroad.

● Delays in Restoring Civilian Rule: Traoré’s about-face on the duration of the transition is another source of controversy. When he took power, he explicitly pledged a return to civilian government by July 2024. However, as that deadline approached, Traoré reversed course, arguing that holding elections would be irresponsible so long as Burkina Faso was partially occupied by terrorists. In his words, elections were “not a priority” until the country could reclaim its territory and ensure all citizens could vote safely. In late May 2024, Traoré formally rewrote the transitional charter to prolong military rule for an additional 60 months (five years). Shortly after, this was further extended: an amended charter signed on 25 May 2024 added a full 60 months (five years) to the transition timeline, effective from July 2024. In plain terms, Traoré can now remain president up to July 2029, and the new rules even allow him to run in the eventual elections – despite earlier assurances that no coup leader would be a candidate. This U-turn has sparked criticism from democracy advocates and regional bodies. Many view it as reneging on his promise and entrenching a new military dictatorship in all but name. Comparisons are drawn to neighboring Mali, where a similar post-coup transition extension has kept military rulers in power. ECOWAS and the African Union have condemned the timeline extensions, but Traoré appears determined to govern on his own terms, indefinitely if security does not drastically improve. For Burkinabè citizens who hoped the junta would be a short-lived corrective, this development has been a serious letdown.

● Human Rights Abuses and Atrocities: Under Traoré’s leadership, Burkina Faso’s security forces have been implicated in some of the worst human rights violations in the country’s recent history. As the army and its auxiliary VDP units have ramped up operations, reports of massacres of civilians by government forces have surged. In April 2023, for example, soldiers in northern Yatenga province were alleged to have summarily executed at least 156 unarmed civilians (including dozens of women and children) in the village of Karma. Witnesses recounted men in military fatigues going door-to-door, killing villagers in retaliation for an earlier jihadi attack – a shocking incident that Human Rights Watch described as “one of the worst massacres in Burkina Faso since 2015.” The government promised an investigation, but over a year later no culprits have been publicly identified or prosecuted. Even more harrowing, in February 2024, Burkinabè troops allegedly carried out coordinated killings in two villages (Soro and Nondin in the Thiou district), resulting in a death toll of 223 civilians, including at least 56 children hrw.org. These mass killings of civilians by state forces – often targeting communities suspected of harboring or sympathizing with Islamist rebels – may amount to crimes against humanity, according to human rights organizations. The Traoré government’s general response to such accusations has been denial or dismissal. Officials frequently label reports of military abuses as “foreign propaganda” or justify harsh measures as unavoidable in a war where jihadists hide among civilians. The junta even temporarily suspended a major international NGO’s operations after it reported on a massacre, calling the report “baseless” and hostile to the military. Nevertheless, the pattern of atrocities attributed to security forces (and proxy militias) has drawn international condemnation. The United Nations, African Union, and human rights watchdogs have all urged Traoré’s government to rein in abuses and allow impartial investigations. So far, however, there is little sign of accountability – fueling fears that the culture of impunity is deepening under the junta, and that Traoré’s “scorched earth” approach to counterinsurgency is victimizing the very civilians he claims to protect.

● International Isolation and Criticisms: Traoré’s defiant stance on the global stage has been a double-edged sword. On one hand, his anti-Western, anti-imperialist messaging has won him enthusiastic fans among populations tired of foreign meddling. On the other hand, it has strained Burkina Faso’s relations with many nations and international partners. The country remains suspended from the African Union and has lost access to some forms of foreign aid and military assistance (the United States and European Union halted non-humanitarian aid after the coups). France’s President Emmanuel Macron has emerged as one of Traoré’s most vocal critics, pointedly linking Burkina Faso’s junta to Russian interference. Macron in 2023 described what he saw in the Sahel as a “baroque alliance between self-proclaimed pan-Africans and neo-imperialists” – making clear he believed leaders like Traoré were in league with the Kremlin to exploit anti-French sentiment. Western officials have also voiced concern that Burkina Faso’s closer ties to Moscow could open the door for Wagner Group mercenaries, with all the accompanying risks of human rights abuses and destabilization (a fear grounded in neighboring Mali’s experience). For Traoré, such foreign criticisms serve as convenient foil: he often cites them as evidence that he is on the right track, angering “imperialists.” In April 2025, a diplomatic spat with Washington illustrated this dynamic. The head of U.S. Africa Command, Gen. Michael Langley, testified to the U.S. Senate that Traoré’s junta was diverting Burkina Faso’s gold reserves for its own enrichment – implicitly suggesting collusion with Russia or corruption. The junta blasted these remarks as lies, and within days thousands of Traoré’s supporters rallied in Ouagadougou in his defense. Protesters at the capital’s Place de la Révolution held up banners with General Langley’s face labeled “liar” and “slave”, waved Russian flags alongside Burkina’s, and chanted “Long live Captain Traoré!”. The demonstration – clearly encouraged by the regime – was a show of domestic strength against foreign censure, with protesters declaring they opposed “predation and economic slavery” by the West. Such scenes highlight how Traoré has been embraced by some as a symbol of resistance, even as others view him with alarm. Regionally, Burkina Faso’s closest ties now are with fellow junta-led neighbors Mali and Niger, while relations with pro-democracy neighbors like Ghana and Ivory Coast range from cool to openly hostile (Traoré’s government even alleged that Ivory Coast harbored coup-plotters against him, a charge that raised regional tensions). The overall picture is that Burkina Faso under Traoré is more isolated from Western and regional institutions than it has been in decades – a situation that carries risks for a country heavily dependent on foreign aid and imports. Traoré is effectively betting that new alliances (with Russia, and perhaps China or others) and self-reliance will compensate for the loss of traditional partners. Whether this realignment will pay off or leave Burkina more vulnerable in the long run is a subject of intense debate.

Domestic and International Reception

Ibrahim Traoré’s leadership has elicited mixed reactions at home and abroad, with admiration and optimism in some quarters, and deep concern or criticism in others. Domestically, many ordinary Burkinabè initially welcomed Traoré’s takeover. Decades of instability and mounting violence had exhausted their faith in the old political class. Traoré’s youth and military background, as well as his populist promises to take the fight to the terrorists and rid the country of corruption, instilled hope in those who felt trapped by insecurity. In the months following the September 2022 coup, public rallies in support of Traoré were common – often featuring youths and women singing praises of the new captain who “saved” the nation. Even by 2023 and 2024, as hardships continued, Traoré retained a core of popular support. Many Burkinabè give him credit for speaking hard truths about foreign interference and for attempting bold solutions (like arming civilians) that previous governments shied away from. “He is young, he is one of us, and he dares to do things differently,” is a sentiment one often hears among his supporters. The invocation of Thomas Sankara’s legacy also boosts Traoré’s appeal – he is frequently likened to Sankara for his patriotism and simple lifestyle. Indeed, Traoré has reportedly cut some of the trappings of presidential luxury (though not to the ascetic extent Sankara did in the 1980s), and he makes a point to identify with the “common man” in his speeches.

However, domestic opinion is not universally rosy. As time passes, more Burkinabè are asking when results will follow the revolutionary rhetoric. For those who supported Traoré solely because of security, the continuing attacks and atrocities test their patience. Opposition figures (albeit muzzled) accuse him of betraying his own promises by concentrating power and delaying democracy. There are also ordinary citizens – especially in cities – who worry that Burkina Faso’s international isolation under Traoré is worsening the economic situation. With France and other partners gone, some businesses have suffered and development projects stalled. An undercurrent of fear exists as well: people have seen journalists jailed and neighbors accused of spying simply for questioning the junta. This has created a chilling effect, where criticism is driven underground. The longer the transition drags on with no clear end, the more this disillusionment could spread.

On the international stage, Traoré’s reception is sharply polarized. In Africa and the global South, he enjoys a kind of celebrity status in certain circles. Over the past year, he has been celebrated in myriad social media posts, YouTube videos, and even music tributes (some authentic, others fabricated by fanatics) as an icon of African renaissance. Young pan-Africanists from Dakar to Johannesburg have lauded him for “standing up” to France and for fostering African unity. Traoré’s close cooperation with Mali’s Assimi Goïta and Niger’s Abdourahamane Tchiani (both fellow coup leaders) is often cited as a positive example of African neighbors supporting each other outside the influence of former colonial powers. In the broader African diaspora, including African-American communities, Traoré’s words on racism and imperialism have resonated, and he’s garnered online admirers abroad who likely could not have found Burkina Faso on a map before. This organic popularity across borders is unusual for a head of state of a small, poor country – “he is now arguably Africa’s most popular, if not favorite, president,” remarked one researcher to the BBC.

Conversely, Western governments and human rights organizations view Traoré with deep skepticism or outright disapproval. The United States, while cautious in its public statements, has reduced cooperation and voiced alarm over Burkina Faso’s tilt toward Russia and the Wagner Group. The European Union has condemned the expulsion of French forces and the abrogation of democratic norms, and it has maintained sanctions that were imposed after the initial 2022 coups. France’s relationship with Burkina Faso went from alliance to animosity almost overnight under Traoré. French officials regularly decry what they call a campaign of disinformation against France in the Sahel, often pointing directly at narratives pushed by Traoré’s regime. In late 2022, after mobs in Ouagadougou attacked French facilities for allegedly sheltering Dambia at a military base, France’s foreign ministry denied such accusation. The tension culminated in the withdrawal of the French ambassador and troops, effectively severing a decades-long partnership. Meanwhile, Russia and China have been more welcoming to Traoré. Moscow, in particular, has given him high-profile platforms (like inviting him as an honored guest to World War II Victory Day celebrations in 2025 and frames Burkina Faso as a country “liberated” from Western neocolonialism. This reflects the broader geopolitical contest playing out, with Traoré clearly choosing a side.

Traoré encourages anti-France sentiment. Source: Free Malaysia Today.

For regional African bodies, Traoré poses a dilemma. ECOWAS has seen three member states (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger) fall to military coups in quick succession, and Traoré has been unapologetic in rejecting ECOWAS demands. After initially condemning Traoré’s coup, ECOWAS has been relatively muted, likely because it has limited leverage and fears pushing Burkina further into isolation or toward Russia. The African Union likewise suspended Burkina Faso’s membership but has sought dialogue. Notably, in 2023 Traoré announced that Burkina Faso, would boycott the West African Monetary Union (WAEMU) meeting, signaling a possible intent to break away from certain regional frameworks as well. Such moves have prompted some African leaders (like Ghana’s president) to caution that the “wave of coups” endangers regional stability and development.

Outlook

As of mid-2025, Captain Ibrahim Traoré stands at a pivotal point in his leadership. He remains a polarizing figure: hailed by supporters as a patriot rescuing his nation from terror and neocolonialism but regarded by critics as an increasingly authoritarian ruler who has yet to deliver on his core promises. Under Traoré, Burkina Faso has undeniably undergone a radical political transformation – breaking from France, embracing new alliances, and pursuing revolutionary economic changes – all in a very short span. These shifts have energized parts of the population and inspired copycats in the region (e.g. young people in other African countries holding his photo during protests). However, the fundamental challenges Traoré vowed to solve – notably the security crisis – continue to exact a heavy toll, and many of his decisions (such as arming militias and curbing freedoms) carry longer-term risks of their own.

In the coming years, Traoré’s leadership will be tested on multiple fronts. Security will likely remain the make-or-break issue for his legitimacy: if his militarized approach yields improvements and allows displaced people to return home, he could solidify his standing; if the violence drags on unabated, public patience may run out regardless of propaganda. Economically, Burkina Faso faces hardship with or without Western aid, and it remains to be seen if new partnerships (like increased trade with Russia or gold-for-arms deals) can compensate for any isolation. Diplomatically, Traoré appears intent on forging a new regional order with fellow juntas, but any instability within that alliance – or a democratic transition in one of those states – could alter the calculus. Domestically, pressure could build below the surface for a return to civilian rule, especially if opposition elements regroup or if segments of the military grow dissatisfied.

For now, Ibrahim Traoré has defied expectations simply by holding onto power and capturing imaginations far beyond his borders. His story – a young captain who rose from the front lines to the presidency amid national turmoil – is still unfolding. Will he follow through on creating a more secure, self-reliant Burkina Faso, or will he join the list of strongmen who seized power with promises of change only to govern through force and fear? The answer will shape not only Burkina Faso’s fate, but also reverberate across the Sahel, where millions yearn for leaders who can deliver both peace and liberty in equal measure.

Sources:

● Farouk Chothia, BBC News – Capt Ibrahim Traoré: Why Burkina Faso’s junta leader has captured hearts and minds around the world, 2025bbc.combbc.com

● Edward McAllister, Reuters – Who is Ibrahim Traoré, the soldier behind Burkina Faso’s latest coup?, Oct 2022reuters.comreuters.com

● Favour Nunoo, BBC News – Burkina Faso extends military rule by five years, May 2024bbc.combbc.com

● David Zuber, BlackPast – Ibrahim Traore (1988-), Feb 2023blackpast.orgblackpast.org

● Human Rights Watch – Burkina Faso: Journalists Arrested in Media Clampdown, Mar 2025hrw.orghrw.org; Burkina Faso: Army Linked to Massacre of 156 Civilians, May 2023hrw.org; Burkina Faso: Army Massacres 223 Villagers, Apr 2024hrw.org

● Mark Banchereau, AP News/ABC – Thousands rally… following alleged coup attempt, Apr 2025abcnews.go.comabcnews.go.com

● Thiam Ndiaga, Reuters – Burkina Faso marks official end of French military operations on its soil, Feb 2023reuters.comreuters.com

● Mayeni Jones, BBC News – Why Russia is cheering on the Burkina Faso coup, Oct 2022bbc.combbc.com

● TRT Afrika – Five unique facts about Burkina Faso’s Ibrahim Traore, Apr 2025trt.globaltrt.global

● (Additional information drawn from: Africanews, Al Jazeera, and official statements.)

Notes: This is my own opinion and not the opinion of my employer, State Street, or any other organization. This is not a solicitation to buy or sell any stock. My team and I use a Large Language Model (LLM) aided workflow. This allows us to test 5-10 ideas and curate the best 2-4 a week for you to read. Rest easy that we fact-check, edit, and reorganize the writing so that the output is more engaging, more reliable, and more informative than vanilla LLM output. We are always looking for feedback to improve this process.

Additionally, if you would like updates more frequently, follow us on x: https://x.com/cameronfen1. In addition, feel free to send me corrections, new ideas for articles, or anything else you think I would like: cameronfen at gmail dot com.